The evacuation of the inhabitants in the neoliberal world-class city

As I write these words, the London Real Estate Forum is under way in Berkeley Square – within, we are eagerly told ‘a 25,000 sq foot pavilion space, bespoke designed by Carmody Groarke’. For the pleasure of partaking in such a prestigious event, delegates are charged £995 +VAT. Clearly, for the ‘investors, occupiers, policy makers and professionals’ attending, the allure of participating in ‘an exhibition of up to 50 major office, retail and residential developments available to let or invest in over the next decade’ is just as essential as it might be for art curators, collectors and institutions of art to attend Frieze Art Fair.

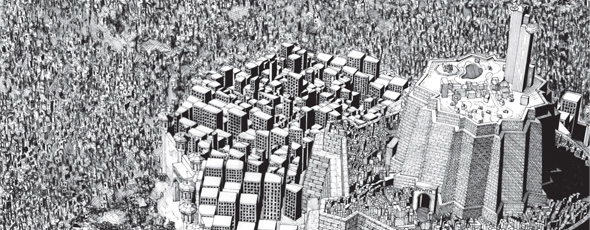

In this overtly suggestive spatial connection between pavilions, the exhibition of objects offered for aesthetic engagement in an art fair contrast the exhibition of models of development offered for financial speculation. All are provided as equal manifestations of creative entrepreneurialism across an aesthetic-financial axis. Here, we can read much into the urban condition in which we find ourselves entangled as common citizens of world-class cities: the city understood as a commodity, of urbanism as a form of marketing and the struggle to imagine the collective symbolic capital that we create in our cities, away from speculative value extraction.

It’s clearly not a haphazard choice that David Harvey’s discussion on how ‘uniqueness, authenticity, particularity and speciality underlie the ability to capture monopoly rents’ in the contemporary neoliberal city is prefixed by the title ‘Art of Rent’. The balance between the appeal of distinction as potentially unlimited added value and the limit to which such value can be extracted before it becomes prey to the homogenising multinational commodification that wipes out the appeal of distinctions, is the ‘artistry’ of the speculative investor, according to Harvey.

These are accelerated and accelerating processes whose aim is ‘to create sufficient synergy within the urbanisation process for monopoly rents to be created and realised by both private interests and state powers’. Here we clearly see that if we are to conceive of a different city than the one that produces and reproduces such mechanisms, we have to first recognise the perceived conflicts between private and public interests as deceptive. We are not in the presence of private theft at the expense of the public, but of a donor-receiver system where the deception, if any, is that of who the beneficiary of such gifts might be.

What is registered at multiple levels is an overt osmosis between markets and state, in the midst of which the citizen (the “inhabitant” for Henri Lefebvre, who coined the concept of the ‘right to the city’) of the world-class city is subjected to the restructuring demands of capital and its hunger for surplus. As Boris Johnson scoffed during his opening speech at the London Real Estate Forum whilst announcing the development of a third financial district for London: ‘You are players in one of the most exciting and most important games of Monopoly ever played.’ Like a medicine which only works through dosage increases that further indebt its patients, the witch doctors of global real estate are escalating their operations in the only way our undead financially-ruled system seems capable of. On this note, a worthwhile if depressing read is Maurizio Lazzarato’s, ‘The Making of Indebted Man’.

It is in these terms that the passage from public to private planning and urban development is hardly worthwhile registering with indignation. The main transformations in urban governance over the last 30 years have been the gradual disinvestment of the public authorities from the public role of custodian of the ‘commons’ (authoritarian as it might have been in the past) and their assimilation of the subjectivities that the market doctrine provided to them as conduits of its directives.

To even begin to think of a ‘right to the city’ in the contemporary world-class city, means not just redirecting the power from private to public administration and scrutiny but also, and primarily, to demand a reconfigured, reformed notion of the ‘public’ as a separate actor from the market (the possibility of a redistributive social justice on a total city scale in the current conditions appears unlikely).

The enmeshed relationship between the markets and urban governance becomes clear when looking at the ways in which the exercise of democratically elected bodies in contemporary urban contexts make extensive use of data, gathered using the same marketing tools that inform advertising companies: sophisticated data aggregation software packages and intelligence solutions which mix different data sets to produce effective visual representations called ‘Geodemographic segmentations’. Examples include EuroDirect’s ‘CAMEO’ and Pitney Bowes’ ‘MapInfo’, which provide classification system segments for ‘billions of consumers in over thirty markets worldwide.’

In short: we are seen as ‘customers’ even for the public bodies who should see us as ‘citizens’. The aversion of markets towards transparent democratic accountability has seeped into the administrative ethos of public bodies who would now dream of delivering social justice as ‘customer choice’ and governing without public scrutiny by its constituents.

The display of cohesion between competitive developers at the London Real Estate Forum, framed by the support of the Mayor of London, highlights the purpose of this strategic alliance where London’s spatial future is presented as an offering to the global market and its parceling of value extraction – orchestrated by a vested interest in bolstering ‘city living’ as a marketing device.

They might as well have been answering the long call that went out at the Singapore World’s Fair in 2010, where swathes of Newham in East London were repackaged and shelved for purchase as a ‘Regeneration Supernova’ for global investors. The last sentence of a briefly public and now removed document from Newham Council regeneration plans, reads: ‘Take your place in the future of London’.

The most disturbing aspect of the subservient and asymmetrical business relationships entertained by private interests and public administrations is the way in which contemporary cities claiming world-class status are shaped by placing its constituents – its citizens – to spectacularise its context: the city is branded as a place of marvel, excitement and wonder, whilst simultaneously marginalising citizens’ actual contribution, opinions, needs and their subjective desires (unless they fit into prescribed roles of consumption that fulfill the patterns of growth and investment central to the world-class status). Among others, Anna Minton’s Ground Control: Fear and Happiness in the 21st Century City and her recent report for Spinwatch are interesting reads.

In the most cynical formulation we could say that the contemporary urban project as it presents itself to us on the ground, particularly when permeated and guided by mega-events such as the Olympic Games and its long-term effect, is one of a structure that attempts to circumvent the rights of the very people at the core of its value and experience.

No clearer display of such sly value extraction in the city exists than the bankrupted trope of ‘urban regeneration’; a suspicious claim for improving people’s lives. Such projects are revealed, for the most part, as desires to spatially reorder the city into a consumption arena, but they overlay very different social realities and conflicts for which the market has no solutions. London’s 2012 Olympic Games provides an unequivocal example. The project’s true ethos was, and remains, that of a brand, but its legacy promised to redistribute the value generated by the public investment into a shortfall of benefits for East London and the city as a whole.

Two sobering pieces of evidence as to the dubious value of such promises are an already existing legacy – that of the ‘adiZones’ – and the widely known case of the Carpenters Estate in Stratford, whose recent escape from the proposed UCL/Newham plans is only one chapter in an ongoing narrative of Olympic-induced regeneration conflicts.

Based on these disconcerting urban realities, where collective symbolic capital is simply pursed as bait for investment rather than a value in itself to be fostered and treasured for the necessary social reproduction of the city as a whole, the proposition of the ‘right to the city’ (‘a cry and a demand’ as Lefebvre would see it) as a way of tackling such asymmetrical distribution of wealth in the city and substantially reconfigure the power relations that produce it, remains a precious asset in an overall argument for a ‘return to the public’, whose voices are multiple and diverse.

As such, the possible formulation of ‘right to the city’ has gone through several transformations, from a ‘radical restructuring of social, political and economic relations’ in its original conception of Lefebvre, to a ‘more and more fascinating slogan.’ In the embrace of institutionalised adoption, it appears that ‘a reformist, managerial, and commoditised perspective of the right to the city prevailed.’ It remains to be seen whether its usefulness as a valuable tool to resist the increasing power of capital over urban life may already have been exhausted in some forms.

One of the key issues to be resolved is that of public information, which was one of the complementing rights in Lefebvre’s original concept of ‘right to the city’.

The transformation of spatial realities produced by speculative value extraction and the ensuing conflicts between the parties involved is only the final chapter of a narrative course that begins far away from public knowledge and deliberation. The hidden trajectories of land aggregation and financial dealmaking, which only surface at the planning stages, are often evidenced too late in the process to be confronted with serious forms of opposition. Some of these narratives were on display at the London Real Estate Forum, screened behind the pricey entry fee.

Crucially, a ‘right to the city’ would mean the provision of a widespread urban pedagogy in which knowledge of the city is available, abundant, free and public. How such urban knowledge might then be articulated into urban practice, and the form and scale of the political communities that might articulate them, will always be a territory of discussion and conflict. At least the landscape ahead of us would be shaped on the basis of horizontally disseminated knowledge across all actors.

By Alberto Duman | albertoduman.me.uk