For the last few weeks I’ve been caught up in the idea of fugitive planning. In their book The Undercommons, Fred Moten and Stefano Harney talk about “an ensemblic stand, a kinetic set of positions… embodied notation, study, score”, which is “practiced on and over the edge of politics, beneath its ground.” The quick melody of these words has haunted me since the election, and this is, undoubtedly, because it rhymes so tightly with what I have been seeing around me. The events of May seem to have released a quiet wave of conversation, a new, gently building movement of talking to make plans, and of planning to escape the unbearable future the new government appears to promise.

But this is also planning as an excuse to escape a more than unbearable present. We call ourselves together so that we may sit in the warm darkness that collects in the back of pubs, and so that we may be there amongst the people who make us feel less alone, less scared, less helpless. Yet no matter how much we feel it, we always sense the need to deny it. No, we say, we didn’t come to be amongst one another, but to produce; we point proudly to our fulfilled agenda, highlight our action points, bask in the sense of accomplishment that comes from the setting of new things to accomplish.

This denial is a symptom of the poisoned bodies we make our politics with; bodies envenomed by the workerism and the heteronormative masculinity that turns us against care, no matter how much we may secretly crave its embrace. Marx said that “tradition weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living”, but it is far more of a poisoning than a bad dream. The rhythms, modes and movements of work and patriarchy cannot be overthrown by some momentary awakening; their potency is a virtue of their piercing pervasiveness. Like toxins they hide within us, and from us seep into our spaces. It is this poison which eats our organising from within, but also this which attacks it from without. When Owen Jones spits bile about “leftwing meetings serving as group therapy” it is this poisoning that moves him. The sad truth is that he has become so used to the toxins of work and machismo that an antidote to them makes him sick.

I haven’t got all that much to say about praxis, I will leave that to others far more incisive and clear-sighted than myself. Instead I am interested in the strategies and tactics already diffuse within the reproduction of antagonistic life. By antagonistic life I mean the living of all those for whom daily survival is synonymous with struggle. Here I am, as I think we all are, forever indebted to Silvia Federici, whose work so acutely identifies “the destruction of our means of subsistence [reproduction]” as being fundamental to the oppressions we experience. The agents of this destruction take a multitude of forms; they can be the racist on our bus, the sexist on our street, the transphobe in our bathroom, the landlord at our door. They are police brutality as much as they are poor pay, they are ill health as much as they are ill will.

The only real way to survive these things is to plan, and that is what most of us do. We go out with friends that we know will have our backs, that will bash back, that won’t take that, and then we go home and take the pills a comrogue had leftover. We huddle close behind our mates to slip through the barriers, we drop the kids with our parents and do the washing at our neighbours. We plan, we organise, and we do so every day, without ever pausing for long enough to call it politics. We have our own practices, our own thinking, our own “embodied notation, study, score.” Fugitive planning is always already a fact of our lives.

What concerns me is the reproduction of this planning, which is also, of course, the reproduction of the antagonistic life which begets it. It feels like surviving is often trying to find something worth surviving for, and if this is true of how we survive it should also be true of how we organise. Thus we come to two affects I feel are essential to the reproduction of our lives: ecstasy and warmth.

The ecstatic is the moment of transcendental intensity; it’s in clubs and gigs when you are lost in the crowd and the music. It’s that feeling when you’re not quite sure where you are, but the reason you go out is to get back there. It’s those moments of ecstasy which help us endure the tearing tedium of survival; they are so precious to us because they offer some release, some escape, however fleeting. This is, I guess, the essence of living for the weekend. Saturday Night Fever is a film about the ecstatic. Can we think of a better avatar of this affect then Tony Manero? “Fuck the future” he says to his boss, “tonight is the future, and I am planning for it!”

Football is also a game about the production of ecstasy. It’s a theatre that writes itself, and that, at its best, always writes towards moments of utter excitement. There has been much talk of late about Clapton FC; a football club where a group of fans called the “Clapton Ultras” have gained a reputation for the inclusive and radical crowd they create on the terrace. Many people have focused on the songs the crowd sings or the flags the crowd waves, but this all misses the point – the most important thing is the crowd itself. Indeed to be more specific what really matters is that which the crowd is consciously producing – the potential for ecstasy. I will never forget the moment James Briggs scored an implausible free kick in Clapton’s cup final against Barking. The feeling was indescribable, but ecstasy is the word that comes closest to doing it justice; a joy multiplied a thousand times by its communising in the crowd. What makes Clapton special is that this feeling can be enjoyed by those excluded from other football grounds, be it by the bigotry of the crowds inside them or the cost of the tickets you need to even experience that. My point is this; that the taste of the ecstatic need not be limited to those straight white men wealthy enough to buy season tickets for Premier League clubs.

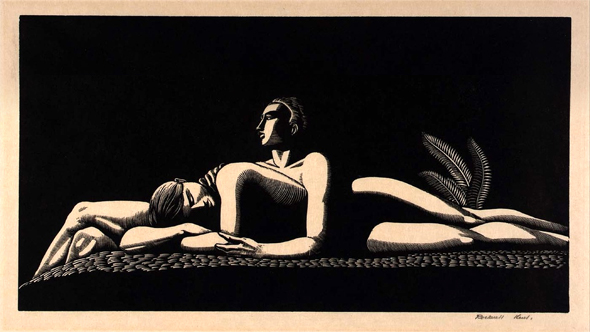

We cannot, however, survive on excitement alone. The ecstatic is only potent when it is surrounded by this other, crucial, affect: warmth. It’s hard to find another word for what I mean by warmth, for it is really a composite of many feelings: safety, closeness, comfort, ease, rest. I suppose warmth is being released from custody to find your friends waiting, but it’s also watching a film in quiet company. Warmth is what makes our struggles bearable, it softens the edges of our anger and our pain and stops them from cutting us up. You tell your friends you have nightmares about cops and they listen to you, tell you that they have them too. It doesn’t make the nightmares go away of course, it never does, but it weakens the shadows they cast on your day.

As I said at the beginning, the potential for warmth resides in many of the meetings we already have. What is needed is to stop fighting its existence. Instead we should embrace the inherent warmth of true collectivity; ask one another about our lives, offer aid where we can, push the contours of our struggles beyond the narrow borders of the “political”. We should not be afraid to linger after the agenda is finished, nor to take pleasure in the simple fact of being there, amongst comrogues, amongst friends.

Perhaps we can imagine communism as the elucidation of this warmth and ecstasy, as their emergence from the exceptional into the everyday. Communisation then appears to us as the conscious attempt to create spaces and collectivities conducive to the production of these affects. Our fugitive planning already involves holding club nights or going to the football, but what I am calling for is for people to accept such activities as fundamental to the reproduction of antagonistic life. Likewise we already trade meds, share nightmares and hold one another, but again these are seen as ancillary acts, as mere consequences rather than constituents of our struggle. My dream is of a politics that recognises the vitalness of ecstasy and warmth, and that comprehends their vitality – their power of life and growth. I can see this power shaping new forms, new organisations, new institutions even. We could have clubs like the CNT and clinics like the Panthers, finding as much excitement in the former as we did care in the latter.

More important, however, is that we allow this recognition to inform all of our politics, that we don’t isolate it in a few of our spaces but rather embrace it in all of them. Together, ecstasy and warmth are the precondition of any revolutionary project; they dim the pain which annexes our dreams and they bring us to those moments which make us dream anew. We must, as a matter of great urgency, escape the logic which says that struggle must destroy us and make us miserable, and instead begin to build cultures which are as loving as they exciting.

Let us reach for the ecstasy beyond us then, allow ourselves to stretch out for it as far as we think we can. But, at the same time, never let our attempt to grasp the ecstatic pull us away from that which is already around us; the great warm embrace of our comrogues. Reaching and embracing by turns, we find that by which we may become something more, more animated, more exhilarated, more cared-for, more loved. In warmth and ecstasy we find the possibility of living a life infinitely greater than that which we currently live.

Our survival may well be radical, but our flourishing is revolutionary.

by Automnia | @aut_omnia

1 Comment