Alan Moore is a writer and anarchist, and the author of Watchmen and V for Vendetta. Having written for us back in January, Moore returns to the OT to discuss anarchy, war, and the roots of the modern education system.

OT: Having previously suggested that many of the problems humanity faces flow from a tiny number of “leaders” and the current political and economic system they maintain, what do you identify as the main problems in the political and commercial makeup of our society?

AM: I think that with the inevitable erosion of those false certainties which shored up the reality of previous generations, we have seen a subsequent collapse in our sense of societal significance and, not entirely unconnected, in our sense of personal identity. We are no longer certain what the social structures we inhabit mean, and therefore cannot gauge our own value or meaning in relation to those structures. Lacking previously-existing templates such as blind patriotism or religion, it would seem that many people mistake status for significance, building their sense of self on what they earn or on how many people know of their existence. This appears to lead to a fragmented and anxiety-fuelled personality as the most readily-adopted option, which it may be imagined is a desirable condition for those seeking to herd large populations in accordance with their own often-depraved agendas.

OT: What does anarchism offer in the way of a solution to these problems?

AM: With its inherent rejection of leaders and hierarchy, anarchy is antithetical to all imposed ideas of status. Neolithic hunter-gatherer societies would mock or ostracise those members of the tribe who seemed intent on engineering a more privileged position for themselves, a practice still maintained in some existing aboriginal communities, perhaps as an acknowledgement of the tremendous social instability that seems to follow at the heels of inequality. In anarchy’s insistence on no leaders is the implication that each man or woman takes on the responsibility of being their own master and commander; the pursuit of these demanding duties being the sole means by which meaningful individual freedom is attained. In repositioning ourselves back at the centre of our own unique subjective cosmos, we may find that our dilemmas with identity and meaning are those born of hierarchical societies. As human beings making our own peace with this extraordinary universe, we could make possible the genuine collaboration between self-determined and splendidly various personalities that I believe must be the basis for all truly viable and equally-entitled cultures.

OT: What do you think has been the effect of corporate sponsorship and ownership on the arts, and what would do you think about the relationship between art, advertising and capitalism?

AM: The commoditisation of the arts, with us since the outset of civilisation, is in my opinion always a corrosive influence. It disempowers the creator, and too often turns them into harmless geldings who’ve forsaken individual vision in the frantic scrabble to be marketable in an art field which, increasingly, is little more than an extension of the entertainment industry. Happy to have a profile, to have work, their only function is as social palliatives. Apparently content with this self-image for as long as it is profitable, artists have abandoned their erstwhile role as the wielders of immense and world-transforming forces. No-one wants to be a bard for fear it might disqualify them from the Booker Prize, and in result our culture lacks an insurrectionary John Bunyan or incendiary William Blake when it could sorely use one. As for the connection between advertising, art and capitalism, or ‘Charles Saatchi’ as I sometimes call him, I suppose that the existence of a thriving marketplace is a necessity when one is looking to sell out.

OT: What are your thoughts on the prospects for mass action, civil disobedience and bottom-up movements? Does collective action still have the potential to change society, or does this kind of ‘demonstration’ amount to just that?

AM: Collective action has tremendous power to change society and, yes, mass action in itself is an expression of that change, even when the protest would appear to be blithely ignored by the authorities as with the stunningly huge protests at the Iraq war. A demonstration is just that, a mass display of disapproval that reminds our leaders of the vast potential powder-keg they’re sitting on; a worrying symptom of unrest within the body politic that it is dangerous or even fatal to ignore. In addition to the prophylactic force which they impose on those who govern us, such movements also have the positive effect of demonstrating that a reasoned opposition to oppression is both possible and necessary. Given that the social orders that restrict us are all pyramidal in their structure, and that the top stones on any given pyramid are those which are by definition the most easily replaced, a bottom-up approach to politics would seem to me to be the only real way of effecting meaningful and lasting change.

OT: What other methods or tactics could be explored with a view to challenging economic, environmental and social injustices?

AM: The current protest movement, being a beneficiary of a post-modern world with all the many overlooked or else deliberately hidden treasures of the past at its disposal, could do worse than pay attention to its disaffected history in the search for useful inspiration. The ideas of Situationism, instrumental in provoking the Parisian student population to prise up the cobbles in 1968 looking for a beach, offer intriguing new ways of relating to the urban landscapes which surround us. The concept of psychogeography, derived at least in part from Situationist conceptions of the city, is a means by which a territory can be understood and owned, an occupation in the intellectual sense. Those able to extract the deepest information from a place are those most able to assert some measure of control on that environment, or at least on the way it is perceived. At the same time, by mining seams of buried or excluded information, it is possible to reinvest a site with the significance and meaning which contemporary town planning and commercial vested interests have removed from it. In my conception of the world, it is this luminous substratum of mythology and meaning that the physical domain is standing on, rather than the reverse. Our advertisers and our politicians seem to understand this fundamental law of magic perfectly, and those who stand in opposition to the ruthlessly asserted worldview of such people would do well to turn such nominally esoteric concepts to their own advantage.

OT: Having left school early and built a career as a self-taught writer and artist, what advice do you have for young people today who wish to pursue their own ambitions, or those who don’t have access to the resources of higher education or training?

AM: Having been recently asked to run a few workshops for excluded kids in Northampton, this is a subject I’ve been thinking about a lot lately. Firstly, I’d say that from the perspective of someone just kicked out of school and denied further education, it would probably seem as if the world has ended…and in terms of the conventional world that schooling was allegedly preparing such a person for, it probably has…it may well be the greatest stroke of luck that person has ever experienced. The compulsory education system widespread across the western world is largely a creation of 18th century Prussian educationalist Wilhelm Wundt. After Prussia’s defeat by Napoleon at the battle of Jenner in 1802, it was decided the main reason for the Prussian army’s poor performance was that the soldiers were thinking for themselves rather than blindly following orders. Wundt suggested a new compulsory education system that would solve this problem by fragmenting the pupil’s intellect, and thus also fragmenting his or her personality. This would be achieved by dividing learning into a whole range of separate subjects without providing any linkages between these isolated areas of knowledge.

Also, dividing the pupils up according to age (and, if possible, gender and religion) would further isolate the individual and make them malleable to authority. This is the origin of modern education, a process which seems mainly intended to alienate individuals from the learning process while at the same time teaching punctuality, obedience and the acceptance of monotony. During the Thatcher era, it was decided that the American secretary of state Robert McNamara’s policy of setting ‘kill targets’ for GIs during the Vietnam War (which had obviously done such a lot to ensure America’s victory in that conflict) should be adopted by the NHS. After this had been effected, with the resultant damage to the health service that entailed, it was decided to implement the practice in the field of education. And here we are.

In being excluded from the current education system, it might be thought that the excluded party has been fortunate enough to be knocked off of a conveyor belt which was at best delivering them to a staid life as a useful worker-unit, and at worst propelling them towards a psychological and intellectual abattoir. Not until we are forced back on our own resources do we learn what those resources are, and having been rejected by an education system which quite evidently wasn’t working anyway can be a perfect opportunity to educate oneself. You can pursue those subjects you are actually interested in, where learning is enjoyable and sometimes actively addictive, and will probably discover that an interest in one subject will lead naturally to an interest in almost every other subject over time. You may even find, as in my own case, that you’re often asked to lecture at the educational establishments you were prevented from attending, where the highly specialised and exam-fixated students will seem baffled and bewildered by the breadth of knowledge which you seem to have absorbed. It’s also worth pointing out that none of the many wonderful artists or writers with whom I’m acquainted have got there through the route of academic qualifications. In practice, most of what is being taught in schools amounts to shoddy and beleaguered lessons on how to become a shoddy and beleaguered teacher, perpetuating a system which for centuries has been geared more to the enslavement of young psyches rather than their liberation.

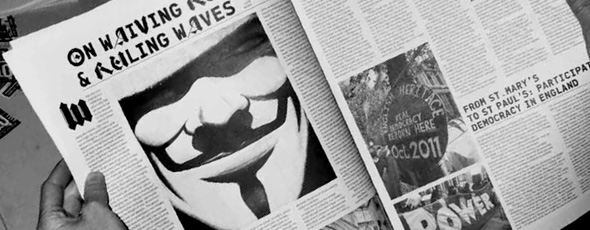

OT: Throughout your career you have been involved in various underground and independent publications. Do you feel that cyberspace is the best platform for this kind of work, or is there still value in tangible ‘underground’ publications today, such as print media?

AM: Given that I do not possess an internet connection, it’s likely that my answer to this question will be biased. While I suppose that there are underground or counter-culture publications which exist online and which may be tremendously effective, my own leanings are toward print media, which seem to me more human and immediate. With Dodgem Logic, when an electronic version was proposed, I found that my initial interest chilled considerably after seeing such a publication. While presumably pitched perfectly at its intended audience and beautifully produced, I personally found the presentation slick and rather soulless, with the interactive elements merely distracting and irrelevant.

Also, around the time that I was thinking about this, my elderly neighbour Elsie from across the street bumped into me and thanked me for the Dodgem Logic issues that I’d posted through her door, informing me that she’d made one of the delicious trifles suggested on our cookery pages and had really, really enjoyed it. At that moment it occurred to me that this was someone who would never own or use an iPad, and that this applied to many of our local readers. I do not believe that everyone is now online and that we are existing in an information-rich utopia. I see a chasm opening between the information-rich and information-poor and, possibly because of my own background, age and prejudices, I believe that something funny, lovely and informative that is available to everyone without the need for a device or internet connection is the option which, to me, makes most sense both emotionally and ethically.

OT: Your work Lost Girls was described as “pornography”, and certainly challenged the preconceptions around this field by exploring new narratives and representations of sex and sexuality. How important is the treatment of sex, sexuality and gender in terms of the overall well being of a society?

AM: Our sexual identities are our most intimate components, and the greater part of those identities exist entirely in the sexual imagination. The governing of sexual imagination, then, becomes a high priority in any system of control. Our current culture involves an incessant bombardment with sexual stimulation and also seeks to associate shame and guilt with any sexual unorthodoxy. I believe that this results in certain individuals being forced into progressively more dark and furtive corners of their fantasy life, and perhaps eventually deciding that they wouldn’t feel much more disgusted with themselves if they were to cross over from the realm of fantasy to actual abusive practice. This would seem to be borne out by the much lower rate of actual sex-crime in those countries such as Holland, Spain or Denmark where no social stigma is attached to the perusal of pornography. While a sexually healthy attitude is perhaps not the single most important aspect of a functioning society, an unhealthy approach to these matters will almost certainly eventually poison every other aspect of the culture.

Boys and girls with an excess of healthy and hormonal sexual energy will have that vital life-force siphoned from them to fuel foreign wars or other violent and fanatical agendas. Better, I think, that we should overcome our shame and squeamishness in talking about sexual imagination and identity, and in the right hands I believe pornography might be a vehicle towards that state.

OT: Last year, Frank Miller (Author of Sin City & the Dark Knight Batman series) described Occupy Wall Street as a bunch of ‘louts, thieves and rapists’, and suggested that if they really wanted to better their country, they would join the army and fight in Afghanistan. You and many other comic writers openly responded that he was out of line; would you care to elaborate?

AM: You have to remember that a certain number of individuals in the comic industry are largely there because they’ve managed to somehow transform abilities with art or writing into a career that guarantees them an extended adolescence. Their worldview is coloured or informed by the simplistic moral narratives which they spend the best part of their creative lives delineating, and they are often careful to avoid any information which would prove disruptive to that way of seeing things. Anybody who had actually spent any time conversing with ex-servicemen would know that they are not the natural enemies of protest movements such as Occupy. For one thing, as I understand it, more than half of the whole homeless population in both Britain and America is made up of ex-forces personnel no longer needed by their countries, and one might indeed suppose that they would have a lot of reasons for supporting protests against the conditions that have so shamefully disadvantaged them. I understand Frank Miller stated his regret that he was now too old to fight alongside soldiers in Afghanistan, but said that if he’d been a younger man he would have been the first to have his ‘finger on the trigger’. Presumably he didn’t hear about the first Gulf War, the conflict in the Balkans or the many other opportunities he could have had to do the right thing and enlist.

I can remember, in the 1980s when the marvellous Joyce Brabner organised Real War Stories for Eclipse Comics, I was amongst the comic professionals who were put in contact with ex-service people with an eye to transforming their personal stories into accessible comic form. I worked with an understandably initially prickly Vietnam vet turned excellent writer named William Erhard, telling the story of how his youthful patriotic idealism had been used to take him to a distant land to kill farmers and fishermen. Bill’s story was a powerful and harrowing account, and anyone who’d listened to it could not have continued to base their idea of modern warfare on a Sgt. Fury comic that they read when they twelve. But then, Frank Miller didn’t contribute to that project. My thoughts on the whole matter are that, if you should be employed in a supposedly creative industry where you spend your day writing or drawing about heroism while rigorously avoiding any real-life application of that quality, you should probably keep your mouth shut regarding people and situations of which you clearly know or understand nothing.