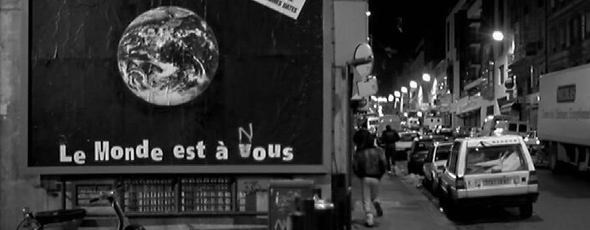

Throughout the course of Mathieu Kassovitz’s seminal realist film, La Haine, the writing on a billboard in the streets of Paris is altered. What at first promised “The world is yours” is reappropriated, with spray paint, to counter-propose: “The world is ours.”

Our considerations of these statements explore the basic assumptions, ideals and actualities of liberty and our rights to – or within – the world around us. The differing dynamics exposed by these alternate statements are nowhere more visceral than in our considerations of life in the twenty-first century city, where the processes of neoliberal commerce are as entrenched and routine as the route we take to work. From commute to workhouse, there is no delineation; and in a world in which the commodity-form stretches into the “out-of-work” hours, how much of our activity – night, day and weekend – isn’t really an extension of this unwavering commute?

Activity in the city is routine, ordained and maintained largely through the coercive ‘metadata’ of commercial custom and worker relations. Like dead metaphors in language – where all poetic potency has been lost as a result of recurrent use – the signifiers of this metadata are ingrained and unobserved, to the point where behaviour in the city conforms, almost completely. As a consequence, much like the inhabitants of Hotel California, the workforce of the city is technically free to check out anytime, but can never really leave. So what’s left to do but to daydream of “Californication” through every ‘white market’ transaction: at work, within our properties and in the bars, clubs and ‘leisure facilities’ the city has to offer.

Of course, there are moments when this daydream breaks. Moments when, more than ever before, the world is yours. Remember what the world meant to you the last time you fell in love. How easily the coercive signifiers of the commute fell apart to reveal a city of possibility – of rule-breaking, pursuit and potential. Those encounters and situations in our lives that are caught up in romantic narratives represent moments of potential when the curtain more readily falls on the otherwise orchestrated city before us – when we encounter, first-hand, the scope of our own liberty and when the façade of concrete and commercial currents that otherwise directs our actions is most readily challenged, and disposed of; albeit momentarily. The point here is to evoke the very real refutation of that old adage – “there is no alternative” – when it comes to possibilities for our lives within the world.

The artist and architect Constant Nieuwenhuys went to great depths to explore and document such alternatives in his conception of New Babylon: a series of elevated zones in cities and in the countryside. New Babylon envisions supported landscapes to cater a nomadic species of play-beings. The real value of New Babylon here lies not in our consideration of the potential realisation of Constant’s vision, but in the very real – and very possible – illustration of the world of alternatives of our own design.

To alternate further, we may find that we don’t need to reimagine the city, so much as reimagine the agents within it. Raoul Vaneigem, Constant’s former comrade in the Situationist International, considered the landscapes of late capitalism as near-vacuous, where space between people and things is populated largely by alienating mediations: the city as a labyrinth “in which you are allowed only to lose yourself. No games. No meetings. No living.” But rather than return the city to the drawing board, Vaneigem instead proposed the revolution of the self, and by extension, the world. Retracted from the concrete vision of projects such as New Babylon, but rooted more in the organic matter-of-fact world of everyday life, Vaneigem proposed the poetic organisation and practice of creative spontaneity; from commute to workhouse, and to the time we spend in the out-of-hours markets. As with moments of high romance, poetic action must take as its foundation a conception of the world as yours, together with the will to practice experimental activity above and beyond the framework of any theoretical model or alternatively imagined city-space.

The visionary writer JG Ballard believed in the power of the imagination to “remake the world”, but this only gets us so far. For Vaneigem, praxis is a necessary component of reconstruction and revolution. Insofar as we tolerate the blueprints of philosophy and the staticity of imagination as nothing more than surrogate daydreams within the confines of our predicament, the writing on the wall will remain the same; the world is theirs. What is required of our relationship with the city is a bridge between Ballard’s faith and the reality of an experimental and poetic praxis that may help to transform – or evoke the transformation of – the self; and the world within oneself.

What might such action look like? These kinds of abstract musings won’t cut it, as spontaneity and action are a part of the mix, but we can continue to ask ourselves: where, within the world of the perpetual commute, may we make greater efforts to expand our liberties, or to poeticise-in-action? Insofar as the agents of the city exist within the domain of everyday life, there is kindling of potential literally all around us. Poetics, gesture, artistry, vocalisation, cooperation, estrangement, creativity: all the avenues of the self are tools for the re-imagination of world.

In the chimerical cities of the twenty-first century, the only writing of substance is on the fourth wall. To break the grammar of dead metaphors that coerce our activity in the city, a new praxis of poetics is required, together with the will to delineate from the perpetual commute. If the signifiers of the commodified world follow only the grammar of dead metaphors, only then can a new poetics, and a poetry of the living, reappropriate the writing on the wall, to reveal: “the world is yours.”

By Mark Kauri | @mark_kauri