Technology is at the heart of contemporary social movements. Activists can bypass the corporate media and post their views via blogs. Police brutality can be easily captured and disseminated across the web to counter the lies of the establishment. I actually came to write this article as a result of an appeal posted on Twitter.

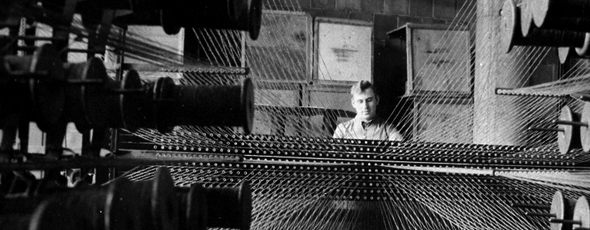

It might seem odd then to suggest that the movements of today have anything in common with – or could learn anything from – the Luddites, a group rarely mentioned other than as a term of disparagement in response to your grandmother asking you whether you tweet much on your Facepage. In actuality, the Luddites were English radicals and as progressive as any social group in history. They were not opposed to technology but rather to the societal problems caused by industrialist’s application of it, to destroy working practices which were integral to many communities.

Britain in the 1810s was a place of real hardship. An economic depression was being worsened by the Napoleonic Wars – financial hardship and expensive foreign wars; it would surely be patronising to point out the more obvious similarities to issues facing us today. The first acts of machine breaking that signified the beginnings of the Luddite movement occurred in Nottinghamshire during November 1811. As the great Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm makes clear, industrial sabotage was an important part of European industrial disputes of the time, having first materialised at the beginning of the previous century.

As such, the Luddite campaign became the latest outpouring of machine-breaking in resistance to modern industrial practices. By the beginning of 1812, the Luddite’s movement had spread to West Riding in Yorkshire and by March it had reached Lancashire. It is always important to recognise that the precise goals of many of the aggrieved workers in different areas of England at the time could no more be explained under one simple umbrella term than those of the varying left-wing campaigns opposed to austerity today.

As with the various Occupy campaigns around the world today, for instance, there were some issues that united the people and their struggle became known under the single banner of Luddism. The term Luddite is derived from the mythical figure of Ned Ludd, a man who was purported to have angrily broken two knitting-frames a generation before his name was adopted by the machine-breaking movement. In his speech at the University of Huddersfield, Kevin Binfield argued that the use of language by the Luddites was reminiscent of modern Occupy movements. It was a malleable term in the hands of both the movement itself – Ludd swiftly became a verb; “to ludd” was to destroy a machine press – and the authorities who benefitted from having rebellious loom workers presented as a single threat to the established order.

This was a period when the British establishment itself was in deep turmoil: King George III’s legendary madness and the 1812 assassination of the Prime Minister Spencer Perceval, by a businessman who blamed Percival for his failings in Russia, deeply shook the status quo. The Luddites’ language gave the establishment further cause for concern; one letter sent to the Vicar at St. Mark’s church from a self-confessed Luddite spoke of, “Bellingham the patriot”, referring to John Bellingham, Perceval’s assassin.

The Luddites were not the reactionary forces that we’ve been made to imagine. Instead, they were fighting for the things that many trade unionists and activists are fighting for today: secure jobs, a survivable wage and improved working conditions. Hobsbawm notes that the tactics favoured by the Luddites, “implies no special hostility to machines as such, but is, under certain conditions, a normal means of putting pressure on employers or putters-out.” And the people recognised this. Luddites were sheltered by those in their communities. There was an “overwhelming sympathy for the machine-wreckers,” Hobsbawm tells us. “In Nottinghamshire not a single Luddite was denounced, though plenty of small masters must have known perfectly well who broke their frames.” The Luddites were true progressives because, like all true progressives, they were fighting for that most radical of goals: a future.

As the movement grew, the full force of the ruling class would be launched against the Luddites and other radical groups. More troops were deployed in industrial towns to counter the growing threat of insurrection than were ever sent with Wellington to the Iberian Peninsula to fight Napoleon; working-class revolutionaries at home scared the rulers of England more than the armies of revolutionary France. Habeas corpus was suspended in 1817 by Lord Liverpool and acts against “seditious meetings” were also imposed. As is the case now, it is when the establishment is most scared that it is at its most brutish; the cloak of liberalism is the first thing to be removed as the fires heat up. Today we must remember that police brutality and state surveillance of activists will only grow, and we should be encouraged when it does for it will show that those who are most frightened of change believe it to be in the air. The spirit of Ned Ludd is alive in anyone who directly confronts any system that seeks to render it worthless.

By James Stanier | @NyeBeverage