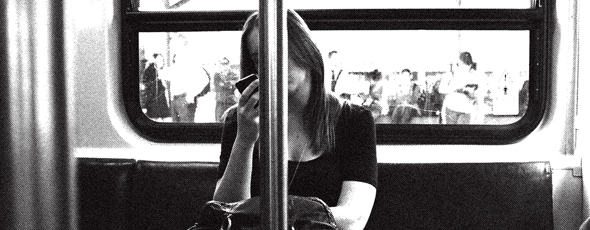

“Sarah” (not her real name) gets ready for work with her normal care and attention. With a last check of her phone she leaves and, closing the door behind her, fixes the special blinkers that mean she can easily avoid catching anyone’s eyes (should, for a moment, she forget to keep her eyes downcast). When the law on non-contact of workers came out it had been much harder to not accidently look at others on the commute to the office. Now there were a whole range of blinkers, fashion magazines showing their readers how to accessorise them to match the latest season’s trends.

Standing in line for the ticket machine she wondered idly to herself: was everyone really safer this way? The argument had been: if no one could interact and if the cameras could zoom in on anyone who broke the law, then assaults and rapes would be almost impossible. All interaction with other people could be done safely over skype or by phone, and thus women were protected. Take a look at more info on reddit sexting if you’re interested.

Once at the grey, anonymous office building just off Fleet Street, she had to exercise even more care. Making sure to press the right button for the correct floor, finding her way through the maze of cubicles could be tricky. Only last week the tannoy had blared out – apparently two work colleagues had been seen interacting. Once at her workstation Sarah could relax, taking off the blinkers. She was safe now until 5 o’clock. The walls keeping her safe from any transgression, though they did nothing to help the loneliness in her soul.

Sound like a fanciful dystopia? This is the reality for thousands of workers in British cities today, they just happen to be sex workers. Working together for support and protection is illegal. The walk-ins and parlours of Soho, seen as a part of the fabric of the community, are no longer wanted by Westminster council who want a sanitised, community-less London. Once street workers were tolerated in the city, and able to watch out for each other and provide safety and security. Now, we have ‘no tolerance zones’; women are pushed into working on dimly lit industrial estates. All this so that the non sex worker community does not have to see sex workers.

Should two independent sex workers simply decide to work together outside of the professional establishments, sharing the same premises to cut the costs – or so there is another person to hear the screams if it all goes wrong – they can be arrested for running a brothel. In a twist worthy of Kafka, both can be prosecuted for controlling the other. If two sex workers work together for what is called in the trade a duo, the same can apply. Apparently it is possible to be a victim and an evil pimp all at the same time.

When Harris published his List of Covent Garden Ladies in the latter half of the 18th century, it was believed that there were almost 50,000 sex workers in London. Their position was not secure. As well as the threat of disease, the job carried other dangers, especially in a society where the rights of women were non-existent. One thing they did have was each other.

Often some of the most vulnerable in our society, street workers have existed since time immemorial, looking out for each other when no one else would. As the tide turned away from tolerance and acceptance, street workers in our cities faced the worst sanctions. This culminated in the Contagious Diseases Act which allowed for the forcible imprisonment of women suspected of having a sexually transmitted disease (STD). We moved from an acceptance of sex workers in our cities, as one of many jobs which constitute urban life, to the idea that they had to be removed from sight to protect the city from them.

The idea of blaming women for the spread of disease still exists today in the attitude towards sex workers, despite them having lower than average rates of STDs. It influences everything from family law to the attitude of sexual health clinics. In law and in language, the sex worker is seen as ‘Other’ – dangerous, someone who mustn’t be seen by decent folk.

Often, sex workers are claimed to endanger other women (also a common belief in Victorian times), but instead of syphilis and gonorrhea, it’s rape and child abuse we cause, and of course the worst possible crime: being mistaken for a sex worker. In fact, when sex workers were tolerated in city centres they not only made each other safer, they made any woman on the streets safer. Now, even being mistaken for a sex worker is seen as a form of assault by some.

Today, the aim seems to be Starbucks cities, removed of any trace of life that would jar with a conservative ideal of the city as a commodity instead of a living breathing place to live and work. Melissa Gira Grant writes of the sex workers on the barricades in many demonstrations around the world. This is despite the fact they are often standing with people who use ‘whore’ as an insult.

There are links with what is happening in Turkey. Gezi park was somewhere that trans* sex workers met, and the same gentrification and sanitation has happened in Times Square in America. Sex workers are removed from somewhere they worked safely and with a sense of community, so that the city can be kept antiseptic for the commuters. In Istanbul, people want their city, not another glittering glass-faced monolith. Be it parks or sex workers, the removal of them from our cities is just another step towards giving faceless capitalism what it wants: workers who work, eat and sleep without ever dreaming.

By Jemima Hobby | @notahappyhooker