Deception and Propaganda in Social Media

A year after the revelations by Edward Snowden, more or less everybody is aware of the astonishing extent of online surveillance. An outcome of this increased awareness is the development of various protective measures, including encryption practices, privacy protection measures as well as the development of anonymised platforms, such as Kwikdesk, an anonymous and ephemeral version of Twitter. However, other aspects of state and corporate control of social media have received less attention. In the face of rising inequality and increasing political mobilisation from the bottom, the ruling class must pro-actively defend the current power structures and a way to do this includes not only surveillance, but also deception and propaganda in social media. The really dark Internet is a reference to this layer of surveillance and disinformation – the spread of false information which intends to undermine, confuse, disrupt, and eventually defuse any socio-political action that threatens to unsettle the status quo.

With surveillance a given, we must now begin to learn about strategies and tactics of deception and disinformation, coming from states, reactionary and fascist political groupings, and corporations.

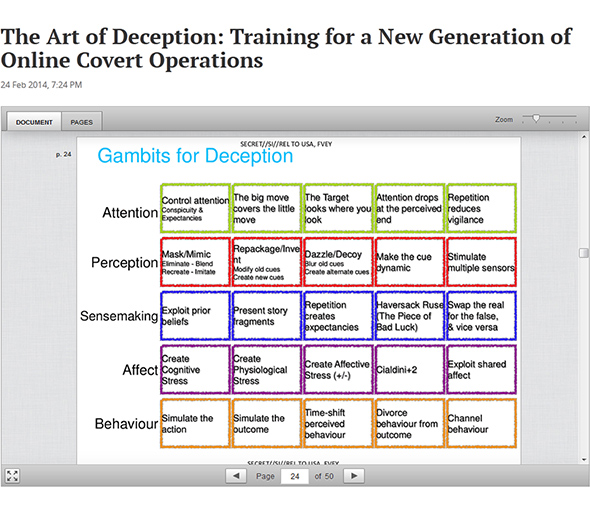

While a lot has been written on the signal intelligence contents of the NSA documents, less is known about the kinds of human intelligence used by government agencies and corporations. In a leaked NSA presentation which would have made Goebbels proud, a British spy agency – the Joint Threat Research Intelligence Group (JTRIG) – explicitly refers to its digital propaganda tactics: the circulation of false information aimed at destroying the reputation of its targets and the use of insights from the social sciences in order to manipulate online communications in line with their political objectives.

The presentation goes on to list techniques for dissimulation or ‘hiding the real’ through ‘masking, repackaging, and dazzling’, and for simulation, or ‘showing the false’ through ‘mimicking, inventing and decoying’; it goes on to refer to techniques for managing attention, infiltrating networks, planting ruses and causing disruption. The aim is to build ‘cyber-magicians’, who can confuse and manipulate ‘targets’. The presentation concludes by estimating that ‘by 2013 JTRIG will have a staff of 150+, fully trained’. Though we cannot be sure of the status of such plans following the leaks, it would be naïve to assume that they have been dropped.

Pic 1: Slide 24 of The Art of Deception, source: The Intercept

Indeed, if anything, evidence suggests that other governments have made use of these or similar techniques, and that they are not limited to spy agencies, but are in fact part and parcel of political and corporate communication in social media. For example, before their overt repression and censorship of social media, Turkey’s PM Erdogan and the ruling AK party, decided to hire 6,000 people for their ‘social media team’. Their task was to follow and mirror social media users, post positive non-news about AK, and question their social media critics.

This is a strategy that has been used by Israel as early as 2009, resulting in the so-called Hasbarah trolls and shills, who bait, question, attack and lie in order to persuade, influence, discredit or disrupt those with opposing views. Online harassment tactics are also used in Greece, where the so called ‘Truth Team’ patrols the Internet, ‘exposing attacks and lies’ against the government. Although, following an uproar, the website and Twitter account are defunct, several Twitter accounts with no overt affiliation or links to the government have undertaken to attack, defame, and harass anti-austerity activists and accounts.

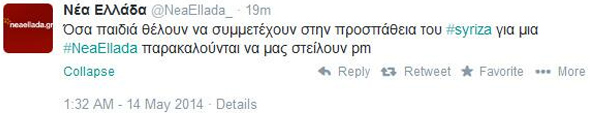

Recently, an unknown user mimicked the account name of the opposition party Syriza’s initiative Nea Ellada and asked supporters to send private messages with their names. Occasionally, such accounts are involved in open threats and intimidation of critics. The fascist Golden Dawn is also spreading disinformation, through fake Facebook pages, and through its affiliated blogs and Twitter accounts.

Pic 2. A fake phishing account (@NeaEllada_) mimics the Syriza-allied account (@NeaElladaGr) collecting intelligence on Syriza supporters (source: @Gerogriniaris).

While the kind of disinformation circulating during the ‘Venezuela protests’ may have backfired because it was so blatant, mud, as Goebbels might have said, sticks. And it is not only governments and political organisations that employ such tactics, but also corporations. The best known example is that of Nestle, and its “Digital Acceleration Team”, which uses software to track negative comments on its water business and subsequently seeks to deflate them, distracting attention or otherwise trying to reverse critiques by ‘engaging’ posters. This is flak, as Herman and Chomsky called it, but directed towards anyone who criticises corporate products or practices.

The impact of these tactics on anti-austerity and other social movements is difficult to gauge. In terms of the personal cost for those targeted, parallels can be drawn with the mental abuse suffered by activists targeted by the Forward Intelligence Teams in the UK. The patrolling and policing of social media spaces through harassment tactics is likely to lead to self-censorship, with people thinking twice about their posts. More broadly, such tactics may lead to widespread distrust, cynicism and suspicion. And this is something that must be avoided.

As recently argued by Paolo Gerbaudo, one of the gains of the Occupy/Indignados movements has been the harnessing of the digital mainstream, and the shift towards what Marta Franco has called “the politics of anyone”. Rather than creating and occupying small pockets of resistance, spreading into the mainstream has been central for recent mobilisations, and I would argue, it should remain a priority. There is, however, a clear tension involved in widening the movement and protecting it from infiltration, deception and disinformation. Yet this should not be prohibitive. New tactics can and should be devised in order to counter those of government and corporate intelligence units.

Counter-tactics should capitalise on the popularity of movements and subject new information to the ‘crowd intelligence’, asking them to evaluate and corroborate it. Verification techniques such as those developed by the now-corporate Storyful, both automated and manual, can be used to verify photographs, videos, data, information as well as Twitter accounts and Facebook pages. Exposure of deceitful tactics alerts people to their existence and deployment. In short, we need to develop an arsenal of counter-tactics that will address and defuse the deception and ‘magic’ deployed by government and corporate spy agencies. When the message finally reaches its destination we must ensure that it is not a lie.

By Eugenia Siapera | @eugeniasiapera