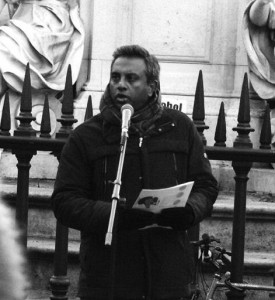

On International Human Rights Day, the Occupied Times speaks to Salil Shetty, general secretary of Amnesty International. Mr. Shetty came to St. Paul’s last Saturday to speak on the criminalisation of protest by Western democracies and to celebrate the day with the occupiers.

On International Human Rights Day, the Occupied Times speaks to Salil Shetty, general secretary of Amnesty International. Mr. Shetty came to St. Paul’s last Saturday to speak on the criminalisation of protest by Western democracies and to celebrate the day with the occupiers.

The Occupied Times: From your perspective, what are the differences and commonalities among the Occupy movement and other movements fighting for human rights across the world?

Salil Shetty: Amnesty believes that people in power – whether in corporations, governments or other spheres of life – cannot abuse this power and then use law to protect themselves, and this is what is being challenged everywhere across the world. The power of this is that it is almost the same issue, what is that people are fighting for in the Middle East and Syria? Their human rights. And it’s exactly what people here are fighting for. How is it different? Frankly I must say, I see more similarities than differences. You could argue that one difference is that the Occupy movement has been focused in the Global North: the rich countries.

OT: What impact can local actions such as this one have at an international level?

SS: All actions are local in their beginning. That is the great thing about social movements; they always start from the grassroots. If the idea is powerful than it spreads and gains relevance at an international level, that’s what we are witnessing through the occupy movement. I hope it serves as a wakeup call for people in the business world and governments around the world to remind them that this level of de-regulation is not sustainable. There must be greater transparency and accountability for the way in which public resources are spent. At the end of the day, even resources of corporations are in part contributed by tax payers, so the fact that there is a big push now, highlighting the necessity of these to become more transparent I think is very important. From an Amnesty international point of view I find the fact of ordinary citizens taking action motivating and inspiring. That’s really the heart of what Amnesty is about; you don’t have to wait for someone else to change things, take action and that will start making change happen.

OT: What do you think about the document recently released by the City of London Police, describing the occupy movement as domestic terrorists?

SS: I am not a legal expert on the specific points that have been made in the document, but what I do know is that it has become habitual for those in power who do not wish to be held accountable, to respond to dissent and criticism, using words such as terrorism and national security to quell protest and stifle dissent. Amnesty International stands for the right to peaceful protest, the right to dissent, which is not negotiable. If you are expressing your opinion in a peaceful way, without infringing the rights of others, than to muzzle that is completely unacceptable.

OT: Do you believe there is link between the increasing curtailment of human rights in the West such as freedom of expression, and the enforcement of austerity measures?

SS: Austerity has been exacerbating an already well-known problem. Amnesty International started becoming increasingly critical of the Western democracies commitment to human rights, post September 11th, during the so-called ‘war on terror’, where we have witnessed an extraordinary rendition of the outsourcing of torture. Then there has been the suppression of rights of certain minority groups such as the Roma in Europe, suppression of women’s rights, LGBTQ rights. Moreover in an economic crisis such as this migrants become the primary scapegoat for public frustrations and the xenophobic forces are unleashed. We are increasingly concerned that these countries who claim to be democracies and claim to be right respecting are diluting their values creating an idiosyncrasy among governments and the wider population. It has been increasingly the case that people have one set of values and governments appear to be following their own separate sets of values.

OT: Today many assemblies around the world are re-writing the universal declaration of human rights. If you could re-write an article what would it be?

SS: I must say generally UN documents are very boring, but the universal declaration of human rights is an amazing document, it’s short, powerful and has all the key elements. I am not one of those who believes the charter should be re-written, I believe the question should be on implementing the document and perhaps deepening it. It’s easy to have these things on paper it’s much harder to make them happen. Earlier the head of Survival made the point that there should be an equal emphasis on collective rights as much as individual rights, which is a fair point. There are also many other aspects to the document that we could improve and deepen. After all, 1948 was a long time ago and the document can definitely be improved. However my main concern is not re-writing the document, but implementing it at the national and grassroots level.