ON TRIAL IN THE ROYAL COURTS OF JUSTICE, FLEET STREET

ON TRIAL IN THE ROYAL COURTS OF JUSTICE, FLEET STREET

Through airport-style security into a hallway of imposing arches and mosaic floors, past a glass case containing relics of Guy Fawkes’ trial, I push open heavy doors and enter the gallery above Court 25, where Occupiers are crammed onto narrow wooden benches.

“All rise!” Judge Lindblom enters the court and the day’s storytelling begins.

As with all the best stories, there are moments of humour and tears too. Pomp is kept to a minimum – no big white wigs but a few “M’Luds”. The judge appears genuinely interested in the peculiarities of the case. He advises the untutored litigants in person, adjusts the schedule to allow every witness a voice and accepts mountains of paperwork, promising to read every scrap of it.

In cross-examination, Tammy is put on the spot about the cleaning of St Paul’s camp before Judge Lindblom’s visit. “That’s normal,” she says. “If I was expecting an important visitor to my flat, I’d tidy up before they arrived.” A down-to-earth answer that pleases his Honour as much as it does the rabble in the gallery. Equally believable is Tanya’s assertion that if she wanted to enter a church to worship, nothing would stop her – certainly not a few tents. Reminding the court that Jesus was a protester and St Paul a tent-maker, she shoots down the notion that the right to worship has been compromised and is backed by Reverend Green, who says that Occupy brings more blessings than curses.

Economist John Christiansen claims that the public debate stimulated by Occupy is absolutely necessary and must be given space to continue. Historical use of the area around St Paul’s for ‘folk moots’ is discussed. Veteran Matthew Horne sheds light on what most have never come close to experiencing – the horrors of warfare – and surprises many by drawing parallels between the devastation of Iraqi citizens’ lives by war and the devastation of British citizens’ lives by debt, poverty, unemployment and home repossessions.

George Barda, litigant-in-person, is overcome by emotion on more than one occasion as he struggles to articulate the enormity of the dangers we face – climate change, resource scarcity, mass poverty – and to impress on Mr Justice Lindblom the urgent importance of the Occupy message. Tears are visible on more than one Occupiers’ cheek, as our hands wave in agreement.

According to the City of London, the Occupy encampment has increased crime figures, reduced visitor numbers and caused an untenable narrowing of the highway… but their statistics fail to stick. Our second litigant-in-person, Dan Ashman, has been out with a tape measure and reports that the narrowest bottleneck on the ‘highway’ in question is not even within the camp. The court hears that police assessments continually rate the risk of serious disturbance at the camp as ‘low’.

The CoL Corporation appears somewhat confused about what they object to – is it the protesters, or the vulnerable and sometimes challenging people who’ve found community in the encampment, or the physical tents? It is tents they are seeking to remove; our QC raises a chuckle when he asks whether it is the tents that are getting drunk, making a noise and committing the crimes that the City complains of.

Dan argues that conventional forms of protest have failed, which is why Occupy tactics are vital. Pressing social need and the desperate importance of the Occupy work are the main thrusts of our defence. Surely these weigh heavier in the scales of justice than petty health and safety qualms and the minor inconvenience of pedestrians?

Fat files of supporting documents are presented to the judge. He has homework to do over the holidays. OccupyLSX is granted a Christmas reprieve and now awaits an early January judgment day.

ON TRIAL IN THE OLD STREET MAGISTRATES COURT OF OCCUPIED JUSTICE

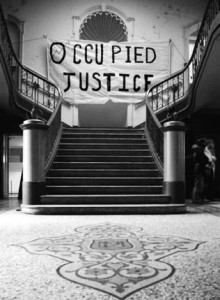

Knock on a heavy wooden door, speak the password, get eye-balled through a spy-hole, hear the drawing back of bolts, step into another imposing hallway. Tigger, my tour guide, gestures to a grand, sweeping staircase. “You want to go up to the courtroom or down to the cells?”

I choose the cells. It’s cold and damp in the basement. Plaster crumbles, unidentifiable stains hint at previous occupants. The cells are equipped with rock-hard sleeping ledges, seatless toilets and metal doors with sliding grills. In the corridor outside each cell is a blackboard with a name scrawled in chalk.

“JP Morgan”. “Tony Blair”. “Goldman Sachs”. “George Bush”. These and other members of the 1% – those responsible for war crimes, ecocide and economic chaos – will soon be under the spotlight at Occupied Justice.

“We’ll be putting them on trial,” Tigger explains. “The accused will be invited along but if they don’t show, we’ll try them in absentia.”

Rumour has it that legal professionals are keen to be involved. A thorough investigation of City of London corruption is promised. The financial services industry will be brought to account in this, the Court of the 99%.

The wood-paneled courtroom is grand. A maze of anterooms, including one with parquet floor and French windows opening onto a balcony, provide plenty of scope for the expansion of Occupy London. Squatters’ rights have been claimed. A peace flag flies from the rooftop. The back yard is big enough to park the Occupy Veterans’ Tank of Ideas.

Despite imminent threat of eviction, there’s a strong sense of fun as well as outrage here, in evidence at the Occupied Justice New Year Cabaret. A theatrical performance sees protesters and party-goers thrown into the cells by a wicked ‘Establishment’ Judge, before reappearing on the grandiose staircase to juggle, dance and recite political poetry to a rapt crowd of visitors. Perhaps the only cabaret where the hecklers call “Process!” and “Mic Check!”. The grand finale – aerial acrobatics on ribbons strung from a stained-glass dome above the Hall – leaves everyone awestruck.

Tigger’s finale is to lead me up spiraling wrought-iron staircases into the night sky. Wobbly- legged on the highest pinnacle of the roof, five storeys above neon-lit pavements, I marvel at the view of Canary Wharf all flash and brash, then turn around to see east London bathed in the lilac-pink of a winter dawn. It does feel like a new beginning.

By Emma Fordham