We are What we Buy. Political Consumerism as Everyone’s Business

We are What we Buy. Political Consumerism as Everyone’s Business

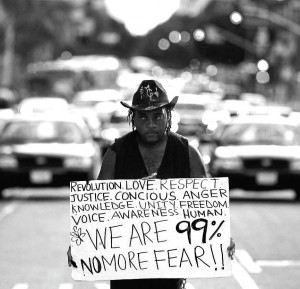

At the heart of the global Occupy movement is the call for radical change based on a rethinking of our current system’s priorities. A central concern in this regard is to reveal the hidden economic and ecological costs of a consumerist society and related individual lifestyles (particularly those of the 1 %). Political consumerism is one way of rethinking our own consumerist behaviour and to influence the public agenda.

Naomi Klein, author of No Logo and The Shock Doctrine, gives on explanation of why it can be fruitful to address companies rather than politicians. To her, it is a question of strategy and corporations are not real targets, but a doorway that activists deliberately choose to wake up politicians and citizens. Effectivity of actions is boosted by the growing importance of corporate image that made companies more vulnerable to even small groups of activists and the rise of the internet as a platform for shared discourse among political consumers. Corporations are mostly targeted because they epitomize general problems in society.

Occupy is supported by fellow campaigners across the globe, in particular by anti-corporate, networked movements and organisations. The anti-consumerist and pro-environment organisation Adbusters is showing solidarity with Occupy Wallstreet (OWS) by listing it as one of their campaigns, and recently, by marrying the annual Buy Nothing Day (BND, 25th and 26th December 2011) to the message of OWS. Indeed, some seasons are predestined for focused action questioning the basis of a consumer-driven society. Particularly around x-mas, advertisements try to convince us how we can show our loved ones how much we care by giving a special brand or status gift. Time to act as conscientious consumers, to challenge the power of corporations and to fight against an ethically blind society.

Buycott vs. Boycott

Political consumerism combines the rationalities of two subsystems: the homo economicus and politicus. The concept originates from the Brent Spar conflict involving Shell in the Northern See in 1995. Often considered as a kind of individualized and global-oriented action, it stands for the choice of producers and products with the aim of changing politically or ethically objectionable market practices. The values of political consumerism match those of Occupy: issues of justice, fairness and social well-being. Similarly, ethical consumerism (sometimes named green consumerism) is the intentional purchase of products and services that we consider to be made with minimal exploitation of humans or the environment. It can be practiced through either buycott (positive buying) or boycott (negative purchasing). If companies like Ben and Jerry’s are solidarizing with OWS, they are actively seeking to convey an activist-friendly image and to initiate buycott strategies of sympathizers.

Although the concept is fairly new, the usage of the market as arena for political activism is quite an old phenomenon. Well-known examples include campaigns against Nestlé or countries like France or the U.S. because of their position on the Iraq war. Whilst boycott is used to express political sentiment, buycott is supporting corporations that represent values like fair trade, sustainable development or environmentalism. However, both boycotts and buycotts can also be problematic, for instance when used against particular groups or minorities (e.g. the “Don’t Buy Jewish” boycotts in Europe at the end of the 19th century).

A Strategy for the 99%?

Another frequent point of criticism is that political consumerism in Western Europe is an activity that belongs to high-resourced people. Being outside of the labour market certainly excludes from such practice. However, as a form of individualistic political action it is particularly attractive to young people as many youngsters are more likely to engage in this form of participation than in demonstration or protest. Whilst these facts point towards the potential to evolve into a more widespread phenomenon, there’s also a less positive side: political actions within the marketplace seem to be more attractive to the majority than visual action and protest. (This corresponds with the notion of life politics (Anthony Giddens) or sub politics (Ulrich Beck)). And how do we challenge a consumerist society if individuals have more power as consumers than as citizens?

It is with no doubt that economic prosperity and individualization go hand in hand. Consumption orientation can thus push a decline in civic participation. On the other hand, political consumerism is always taking place on the intersection of individual choice and collective action. Historically, consumer boycotts were often realized by groups and collectivities, like women (who, to borrow the cliché, are in charge when it comes to shopping). Apart from the youngest, people aged between 35 and 55 as well as students and (probably less desperate) house wives are most likely to be amongst political consumers. A higher degree of global orientation and a sense of global solidarity is significant.

Occupying the Paradigm of Consumerism

Enforced political consumerism should be considered as serious instrument in the occupation toolbox. One role of Occupy movements around the world is to inform about market-based political strategies. Social movements are fundamental to providing such signals to the public, but also to producers, who otherwise would not know too much about their consumers’ preferences. Strategies to put breaks on consumerism through symbolic or visual signals are flash mobs, mall sit-ins, community events or walks of shame as extended boycott (a funny way of raising awareness of which companies not to support). We occupy, as the motto of Buy Nothing Day emphasizes, the “very paradigm that is fueling our eco, social and political decline”. Fasting from hyper consumerism and rethinking consumer decisions, we can confront transnational corporations, demand more transparency in commodity chains, inform about greenwashing or develop political consumerist toolkits.

One central aim should be to raise awareness in individuals (including ourselves) to take responsibility for ecological and ethical footprints. Reflective consumer action is not self-oriented, but based on concern for society as a whole. If Occupy is a mechanism to change the way we think about what we as individuals want, it will have the power to influence collective values as well. So far, the movement has been immensely successful in provoking discussion and getting people thinking about methods of resistance. In the best case, it will initiate profound change in society towards an ethical assessment of business and government practices, including consumption practices on the individual level.

By Judith Schossboeck