The Occupied Times meets leading non-orthodox economist, David Ruccio, Professor of Economics at the University of Notre Dame, Indiana. His Occasional Links & Commentary blog can be found at www.anticap.Wordpress.com.

The Occupied Times meets leading non-orthodox economist, David Ruccio, Professor of Economics at the University of Notre Dame, Indiana. His Occasional Links & Commentary blog can be found at www.anticap.Wordpress.com.

OT: You’ve been following Occupy Wall Street, what are your thoughts on it so far?

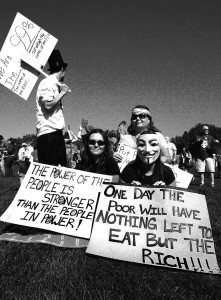

DR: My first reaction was: this is the movement we’ve been waiting for. We’ve been expecting it because of the deteriorating economic and social conditions since the economic crisis first struck in 2007-08. How much longer, we thought, were the 99 percent supposed to put up with growing poverty, unemployment, home foreclosures and budget cuts, while large financial institutions were bailed out and corporate profits soaring?

OT: Has Occupy got legs? Or will winter kill it?

DR: Yes, the movement has legs. The winter won’t kill it. My sense is that the movement will morph and change in the coming months but it won’t be going away anytime soon. Already we are seeing some of those changes, with the emergence of extensions of the movement, such as the Occupy Student Debt and Occupy Our Homes campaigns.

OT: Do you see a coherence in Occupy’s many forms?

DR: One of the extraordinary features of the Occupy Wall Street movement is that it has no central direction, and yet it has a profound and fundamental coherence. All the occupations have occurred in the name of the 99 percent: all those who haven’t benefited from the current crises in capitalism but, instead, who have been forced to pay the costs of those crises.

OT: Do you sense anything new about the movement, or is it an age-old howl of protest against injustice and exploitation?

DR: In many times and places, the masses are the ones who have made history, when they stood up to protest injustice and exploitation. They did it in Paris in 1871 and again in North Africa in 2010, to choose but two examples. So, in that sense, the Occupy Wall Street movement is a continuation of, as you put it, an “age-old howl.”

What’s new, at least in terms of recent U.S. history, is that people are coming together, beyond a particular plant closure or environmental disaster, to express their resentment at something larger and more abstract — the power of Wall Street and large corporations to force the 99 percent to pay the costs of the decisions made by, and on behalf of, the 1 percent.

This raises the stakes: it indicates there’s something fundamentally wrong with the system as it is currently constituted, and that new forms of democracy — political and economic democracy — need to be invented. It’s a kind of break, a qualitative leap, which challenges and transcends business as usual. That’s what’s new about this movement.

OT: We hear rumours of a more profound economic collapse in the Spring…

DR: I do think there’s another collapse on the horizon, especially given the mounting costs of austerity policies and the failed attempts to stitch together a solution for sovereign debt in the euro zone.

Even if that collapse doesn’t occur, we’ve already lost a generation to increased poverty and unemployment (and all the attendant costs on people’s health, schooling, family life, and general social welfare) and even a quick recovery won’t solve that. And the quick recovery that keeps being promised is nowhere on the horizon. Instead, I expect the Second Great Depression to continue for years to come, and for its negative effects to be felt for generations to come.

OT: What part can academics & professional economists play in protest?

DR: It seems to me, the majority of academics and professional economists have either ignored or downplayed the significance of the Occupy movement. Many of them haven’t wanted to be identified with ideas and activities they think are perhaps well-intentioned but ultimately wrong-headed.

OT: So, too much Occupy could be damaging for an academic’s professional health…?

DR: The fact that academics have either attacked or shied away from active involvement in the movement is part of a much larger problem. It stems from the emergence of the corporate university, in which academics are encouraged to focus on publishing in specialized journals and ignore what is going on in the world, and, in the particular case of economics, from the arrogance of mainstream economists, who pontificate on the truths stemming from their elegant, formal models and who regularly attack the economic ideas that are produced and disseminated by noneconomists, within the world of “everyday economics.”

OT: You say that maybe it’s time to “occupy the teaching of economics” – what do you mean?

DR: For the most part, economics is taught as a singular method and set of conclusions, mostly having to do with the individual and social benefit created by private property and markets. In other words, in the name of Science (in the singular), the teaching of economics has become a celebration of capitalism.

The teaching of economics does often introduce students to debates, but the debates are confined to narrow limits: private property and public goods, free markets and regulated markets. Most courses don’t teach that economists can use a wide variety of different theories and methods to discuss issues like exploitation, different ways of appropriating and distributing the economic surplus, unequal power, discrimination on the basis of gender, race, and ethnicity, uncertainty, ecology, and imperialism, to name just a few.

What I mean by “occupy the teaching of economics” is opening up the courses to contending perspectives; different economic methodologies and notions of justice, instead of asserting that economics is based on a singular methodology and is divorced from ethical concerns.

I’m talking about a way of teaching economics that would respond to the issues raised by the students who walked out on Gregory Mankiw’s Ec 10 class this past fall at Harvard University and to the tens of thousands of students who, every year, are forced to learn in an uncritical fashion the very economic theory that created the conditions for the Global Financial Crash and the Second Great Depression.

OT: If you could have Occupy achieve one thing, what would it be?

DR: I think the Occupy movement has already achieved what I wanted: it’s disrupted and changed the terms of the existing discourse. The opposition between the 1 percent and everyone else has put a whole host of items on the agenda, especially the increasingly stark and actually grotesque levels of inequality in the distribution of income and wealth within and across countries, that had been largely ignored within mainstream discourse.

And if you pushed me a bit further, I’d say I want one thing: a growing commitment to the idea of engaging in a “ruthless criticism of all that exists.”

OT: How can a broad-ranging movement like Occupy engage in “critical thinking”?

DR: It’s easy, actually. First, there wouldn’t be an Occupy movement unless critical thinking had been taking place. The people who started the movement and those who have since joined were already thinking critically about the economic and political institutions that created the current crises.

People are connecting the dots and asking critical questions about, for example, the relationship between economic and political power, the role unemployment plays within capitalism, and how workers themselves are quite capable of making the key decisions about what should be done with the surplus they produce.

In the past, the pact with the devil meant giving control of the surplus to the top 1 percent as long as they made decisions to create jobs, fund schools and healthcare, and take care of the natural environment so that the majority of people could lead a decent life. But, as has often been the case, those at the top broke the pact (simply because they had the means and interest to do so) and now they’ve lost their legitimacy to run things.

OT: Some people say the system is broken, others say it’s working just fine (for a very few) – what’s your feeling on this?

DR: My own view is that the system is broken precisely because it’s only working for a tiny minority at the top. Even more: it’s broken to such an extent that fixing it—which is what the elite is trying to do right now — involves imposing costs of austerity on the 99 percent that are so onerous it’s time to think about making some fundamental changes.

OT: These austerity measures: are they working? Are they a way forward?

DR: Austerity measures have not worked, in any region or sector in which they’ve been tried — from Michigan to Greece, from education to healthcare. There are simply no examples of austerity success.

Austerity creates economic contraction, and therefore makes it impossible to lower government budget deficits. That’s because austerity leads to lower government revenues from reduced economic activity. At the same time, there are increased demands on government services from the newly poor and unemployed.

Austerity measures can’t possibly work if the goal is to create economic conditions that benefit the majority of the population. The whole point of the kinds of austerity measures that have been imposed in recent years is to make workers and their families pay so that wealthy individuals and large corporations get to obtain (through increased profits, management salaries, and dividends) and to keep for themselves (through lower taxes) a larger portion of national income.

OT: Do you think society has lost control of its banks & corporations?

DR: It’s not clear that society has ever had control of its banks and corporations. There have been moments, such as during the regulations imposed during the New Deal in the United States, when society had a bit more control. Such regulations, like those contained in the Glass-Steagall Act of 1932, were created in order to protect banks from themselves, and to protect the rest of the economy from the banks. The problem was, the Act left in place the interest and means on the part of the banks to work to repeal those regulations, which they finally accomplished in 1999.

Other regulations were stripped away with the ascent of free-market or neoliberal conceptions of capitalism. The proponents of neoliberalism, such as Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan, even went so far as to argue that society doesn’t exist—only individuals and their families. Under such conditions, social control over banks and corporations became virtually impossible, and we are now paying the costs.

OT: Is there such a thing as a free market, or is there always a plutocrat’s thumb on the scales?

DR: Markets can’t exist without some form of government intervention — for example, to pass and enforce laws concerning property and contracts, to create money, to regulate public and private debts, and so on. The anarchy of private markets needs some form of government regulation in order to keep working.

And if government and markets are not separate spheres, it’s easy to see how the “thumb on the scale” in either sphere affects the other. A winner-take-all economy creates a winner-take-all politics, and vice-versa. Donations to politicians and political parties by wealthy individuals and large corporations lead to policies that benefit those same individuals and corporations. That’s why the Occupy movement has criticized the ways in which the 1 percent’s “thumb on the scale” negatively affects the 99 percent within both the economy and politics.

OT: Will the 99.999% ever overthrow the plutocracy?

DR: The lesson from history is that all plutocracies, when their time is up, get overthrown.