You are at dinner, feeling self-conscious. You haven’t been out in months – it’s a luxury you cannot afford since you struggle weekly to meet your living expenses – but it’s an old friend’s birthday who you haven’t seen in over a year and you’ve been feeling guilty about this.

You are at dinner, feeling self-conscious. You haven’t been out in months – it’s a luxury you cannot afford since you struggle weekly to meet your living expenses – but it’s an old friend’s birthday who you haven’t seen in over a year and you’ve been feeling guilty about this.

But you are already regretting your decision.

She has a good job now, earns a high salary, has flash new friends. The restaurant looks uncomfortably expensive.

You decline a starter, pick the cheapest item on the menu as main – ignoring the thought that you could feed yourself for a week for the amount it costs – and ask for a glass of tap water to drink.

No such austerity for her new friends however! They are clearly determined to enjoy themselves: aperitifs, the best wine, starters, side dishes, dessert, coffee, brandy? Why not! Hell, it’s a shame they don’t sell cigars!

“Oh, I’m not really hungry,” you lie several times when queried about your failure to tuck in.

Towards the end of the meal you hide in the bathroom for a few minutes to get away from your empty place setting. This has been one of the most miserable evenings of your life. To add insult to injury, you’re still really hungry.

You return to the table to find people beginning to stand and putting on their coats talking about continuing the evening in an expensive bar. The bill sits in the middle of the table, already smothered in cash. “Don’t worry about calculating it,” your friend explains over her shoulder as she breezes past. “We couldn’t be bothered to work out who had what. We’re splitting it.”

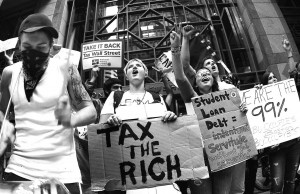

Does this remind you of austerity Britain?

When the coalition government announced that the party was over and we’d all have to pay the bill, writer Neil Root quipped, “What party? Well nobody invited me.”

The phrase “we’re all in this together” was coined by George Osborne while announcing we’d all have to tighten our belts – then he jetted off to go skiing in Klosters. We are not and we never have been all in this together. Conservatives – most of whom have never known and will never know what it is like to live in financial dread – love to take the moral high ground when it comes to debt.

The nation’s debt, they tell us, is a bad thing, like personal debt, and must be paid off in full – like a credit card. The homely metaphors of personal finance are intended to disguise the rabidly ideological nature of their policies.

Reflect for a moment on the paradox that they say this, yet their scheme to pay off the deficit involves increasing the personal debt of every household in this country.

They say this, as though personal debt were a bad thing, yet they refuse to back schemes tackling extortionate lenders of personal credit. Indeed, many of them see fit to endorse companies charging interest rates well in excess of 1000%.

They ignore the economic reality that savage cuts are not going to bolster economic growth. Worst still, so far, everything they have done supposedly in the name of saving money turns out to be more expensive than the systems they replace, such as their devastation of further education.

Only a deluded zealot could look at a country in which people are cutting back on food because they cannot afford to meet their basic needs, where people are committing suicide in despair as their benefits are cut off – and, seeing all this, continue to insist that market forces ensure the best outcomes.

What kind of a sick individual could look at a country in which millions are priced out of home ownership and private rents are soaring then decide that the appropriate response is to cut support to those in social housing, refuse to regulate private landlords and to criminalise squatting?

Each “reform” proposed in the name of saving money turns out in fact to be just another transfer of public wealth into the hands of the profiteers of private enterprise.

This is not about balancing the books – it’s about using a crisis to keep the rich living in luxury even if it means squeezing every last penny out of the rest of us, seeking profit in areas of life that were once immune to the rapacious demands of the market such as health, education and basic social care.

For the privileged in the cabinet, austerity means perhaps only spending ten days skiing in Klosters rather than two weeks. For the rest of us it means eating less because food costs more, not turning our heaters on over winter until it gets too cold to move, walking miles to work because we cannot afford transport.

The question for those opposed to the current government is this: do we hide in the bathroom and try and duck out of the restaurant without paying – hoping enough people follow us to resist the forces of the state – or do we demand those complacently walking away from the table come back and negotiate a fairer deal?

By Tim Hardy of www.beyondclicktivism.com