Activists involved with UK Uncut, Occupy, community organisations and trade unions are about to launch a nationwide campaign – called PAY UP – against highly profitable UK companies that pay some of their staff only the bare minimum. CEO pay, and the focus on the top 1% gained a lot of traction in 2011, but 2012 needs to focus on the 99%, or rather about the low and stagnating pay for the bottom 10-20%. Here are some reasons why:

Wage trends: 1945 – 1979

Let’s take ourselves back to 1978. In the 30-odd years since the end of the Second World War Britain saw an unprecedented decline in inequality. This didn’t simply come about because that period saw the modern day welfare state created; it also saw the labour movement take home a steadily increasing proportion of national income. In 1910, the richest 0.1% of the population took home a whopping 10% of all national income. By 1978, that figure had dropped to a more modest 1%.

A year later, in 1979, Margaret Thatcher rose to power and began her radical programme of neoliberal market deregulation that came to define global economic policy for the next 30 years. The financial markets were freed up, tax rates for the richest plummeted, stringent anti-union laws were put in place, and business was shed of a variety of ‘red tape’ regulation. Thatcher believed that Britain’s economic problems were in part down to the increasing strength of the labour movement. The fightback by those at the top was on.

Wage trends: 1980 – 2012

Now fast forward to 2012. Over the past 30 years, top wages in the UK, as well as other major European and North American economies, have rocketed skyward. Last year the High Pay Commission detailed examples of how some FTSE 100 CEOs’ pay and bonuses have risen by 4,000%. Even in 2010, the average CEO pay in the FTSE100 went up by 49%.

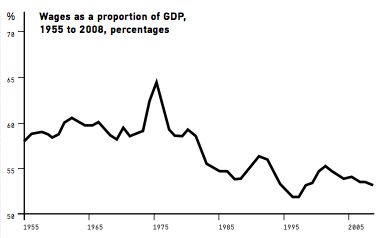

At the same time, the UK and the majority of other Western economies have seen gross wage stagnation for those at the bottom end of the pay scale. The situation is most acute in the United States, but as the accompanying graph shows, the steady fall in income share that the UK labour force has been handed since 1979. In relative terms, millions of people in the UK have been getting gradually poorer, while those at the top have seen their pay packets and profits boom. The introduction of the National Minimum Wage in 1998 certainly improved pay for the lowest paid, but some figures show that over the past 10 years, wages have decreased in real terms by around 10% for those on the minimum wage, as inflation has outstripped growth in pay.

The rise of credit, debt and government wage subsidies

The real crisis in the UK is at the bottom end of the pay scale. When the Tories stand up and say ‘work must pay’ they are criticising a system where some households can receive more in benefits than in wages. The scandal is not an over generous welfare state, it is that work itself does not pay. People are going to work and not even earning enough just to feed their children, to pay the rent and the bills, let alone having a disposable income. The Joseph Rowntree Foundation has shown how the number of children living in ‘in work poverty’ has risen to 2 million.

While wages have been stagnant, we’ve seen energy and food prices soar, as well as the decline of social housing provision, and the rise of market rates in the private sector.

The past 30 years has seen wage rises replaced with credit cards, loans and rising household debt, causing families to always be on the lookout for how to make 5000 fast to use for debt repayment. Some economists have analysed how the US housing crash in 2007 rested on the issue of low wages which creates the need for workers to borrow money to make ends meet or to maintain living standards. The banks then turned these debt packages into complex “sub-prime” financial debt packages to trade and make a tidy profit off. In 2007/08 that debt bubble went pop.

A flagship New Labour policy was the Working Tax Credit (WTC). This is money given to those in work, on low pay, to top-up their wages in order to make ends meet. Some figures suggest that £15bn a year is currently spent on WTC. WTC has provided a vital lifeline to millions of people on low pay, but in the cases where individuals work for a private company, WTC mean the government is subsidising the profits of the private sector. Ironically it is actually the failure of the market to provide a living for people that creates the need for a strong welfare state.

PAY UP

A lot has been said over the past four years since Northern Rock collapsed about the unfairness, greed and inequality of financial capitalism. This anger should not just be reserved for the banks, but extended into the wider economy and back towards a more fundamental discussion about the relationship between labour and capital, workers and bosses.

At the end of 2011 a light was shone onto the bumper pay packets of FTSE100 bosses, and the disgust about bankers’ pay and bonuses is well known. However, an even sharper light now needs to be shone onto low, poverty wages. If a CEO receives a million pounds less this year this will not actually result in any benefit for most people.

Big business in particular can afford high wages. Profits are booming, and some economists estimate that the cash reserves that have been built up by the private sector stands at an eye watering £700bn.

Pay rises should be one of the many steps towards fighting the inequality of capitalism. We hope to build an effective alliance between social movements and workplace organisations that can achieve some concrete action on pay. And we want to popularise wages as an issue, alongside casino banking and tax avoidance in the post-2008 critique of capitalism.

By Daniel Garvin (@daniel_garvin)