Celebration of the international labour movement across the globe has taken on many different moods depending upon the political context of the time, sometimes celebratory, at other times volatile. Today, the stakes are high, and the struggle is of vital importance.

May Day originated as a commemoration of the Haymarket Massacre of 1886, which took place in Chicago during a general strike for the eight hour day. As the police marched on the demonstration in order to disperse it, an unknown person threw dynamite at them. The police opened fire in return, killing several demonstrators as well as some police in ‘friendly fire’.

Since then, the 1st of May has seen many significant historical events and attempts by right-wing governments to subvert or silence the message of worker solidarity. One such move last year was the current government’s proposal to scrap the bank holiday.

This year, May Day takes on a different dimension, with the Occupy movement and groups like UK Uncut joining the workers, students and more traditional bodies. The need for international solidarity is greater than ever. Fiscal cleansing, ruthlessly imposed on the Greek people by leaders with no democratic mandate, has slashed wages by 30 – 45% for government employees. Spain, Italy, Ireland and Portugal are deep in crisis, while youth unemployment and recession continue to blight the UK.

The past month has seen some interesting developments across western Europe. The Dutch coalition government collapsed after the far-right minority party withdrew its support for austerity measures. In France, Nicolas Sarkozy lost the first round of voting to François Hollande, who opposes Germany’s austerity agenda for the Eurozone. Here in the UK, George Galloway pulled off a stunning victory in the Bradford by-election, also running on an anti-austerity, anti-establishment ticket. Could it be that after four years of failure since the crash in 2008, leftist politicians are finally articulating alternatives to austerity?

As encouraging as it is to see shifts away from the Ponzi-scheme economics that have dominated Europe for several years, the devil, as ever, is in the detail. The results of the French vote showed a worrying increase for the Front National candidate Marine Le Pen – and Hollande’s victory came partly at the expense of the genuine leftist candidate, Jean-Luc Mélenchon, who was soundly beaten by Le Pen on an anti-immigration platform, despite encouraging pre-election polls. Hollande might yet turn out to be France’s answer to Nick Clegg.

Voting trends away from a colourless, technocratic centre imply growing disquiet with economic globalisation. If properly channeled, this discontent could be directed towards building a radically progressive and more equal social contract throughout Europe. The danger, however, today as in the past, is when people are drawn instead to populist and reactionary voices capitalising on uncertainty, using the politics of demonisation, nationalism and militarism.

Periods of crisis always offer an opportunity to a range of ideologues and demagogues. We’ve already witnessed the scapegoating of students, the disabled and OAPS. As austerity measures deepen, will British politicians increasingly point the finger at immigrants, as they are doing across the channel in continental Europe?

The global Occupy and Indignados movements point to a left wing resurgence, often rich in numbers but, according to some, lacking in direction. May Day offers an opportunity to deepen our ties with the worker movements, building an alliance between unionised and non-unionised people. Indeed, over the last 30 years, huge increases in service sector jobs (often replacing public service and manufacturing jobs) have led to a large non-unionised working population. While many occupiers are also unionised, the movement offers a vessel for many without representation, which could significantly change the state of play if brought together with established antagonistic means. In Spain, Greece and the US, occupiers, students and young dissenters have formed close ties with unions and other activist organisations. If the Occupy movement is to be sustained, these kinds of alliances will be fundamental.

That doesn’t mean, however, that we should be uncritical of union leadership, or exchange revolutionary energy for reformist compromise. Since Thatcher not only crushed the unions but also set about destroying the environment within which they could operate, union leaderships have largely come to resemble the classic out of touch managerial class of neoliberal capitalism. Times are changing, and unions must change with them.

Union leaders should be bold enough to move beyond defensively protecting their members’ rights within a power dynamic where they cannot win. They should seize the opportunity a crumbling status quo presents them to advocate alternatives to reshape society as a whole, rather than just getting the best deals for their members. Solidarity among unions demands that there be no unilateral deals with governments, selling out other unions and reinforcing the defeatist narrative of the left. Unions should open their doors to the fast-growing and increasingly radical sections of society, namely, the growing number of unemployed people, particularly inner-city youth. Their justified anger could be a powerful catalyst for change.

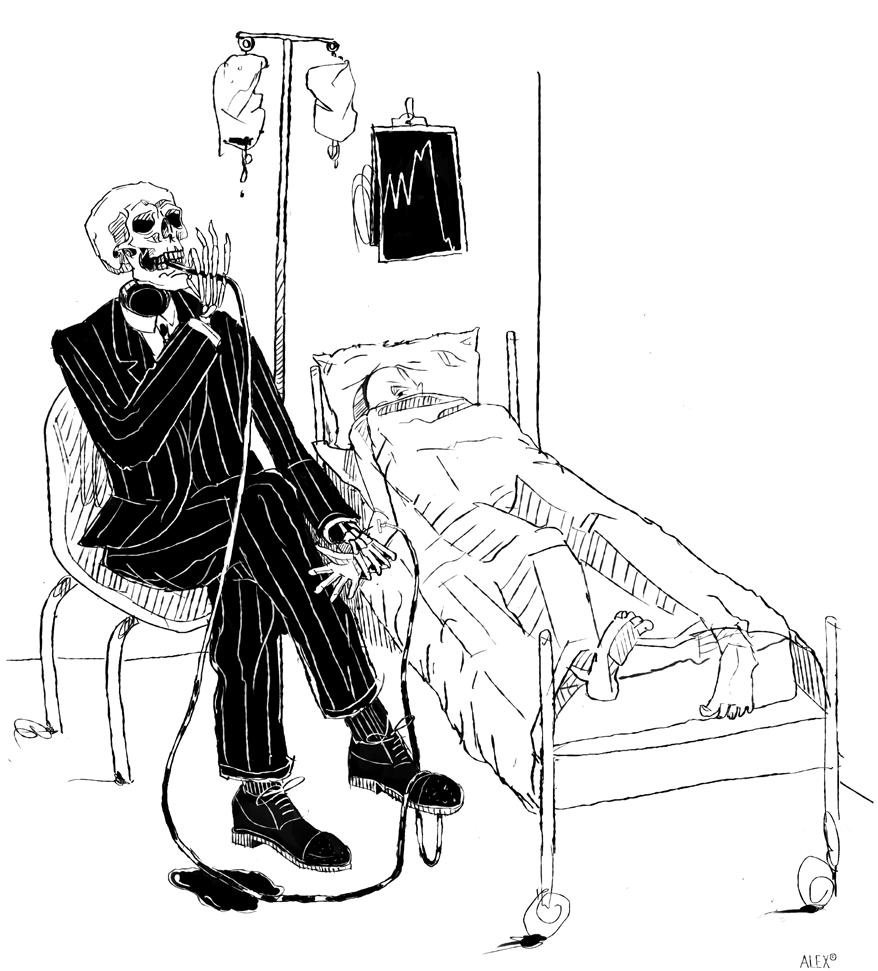

If union leaders prefer to wait for the Labour Party to become a force for change while workers continue to foot the bill, then those who desire radical change must regain control of their unions from the bottom up. For too long now, the neoliberal paradigm has successfully pitted worker against worker and “native” against immigrant, whilst hiding a simple reality: the answer to the problems of society lies not in out-competing one’s peers for a piece of the pie, but in confronting the parasitic policies of the 1%, and besieging the tower which dominates the economic and political system. The solution is not the pursuit of special interests but the politics of the common good. Neoliberalism is bleeding society dry, feeding upon the worst instincts of human nature and destroying the best – the qualities of solidarity, altruism, interrelationship with nature, meaningful work, and respectful coexistence within our families and communities. As austerity further drains the country, and we sink into a double-dip recession, the question remains: how much blood does the patient have left? Let’s make sure that May provides the first of many transfusions.

Illustration by Alex Charnley