Why would King James, famous for his anti-democratic machinations, his shameless financial extravagance and his costly military misadventure, want the following in the Bible?:

Why would King James, famous for his anti-democratic machinations, his shameless financial extravagance and his costly military misadventure, want the following in the Bible?:

“The meek shall inherit the earth”

This is spin that would make Peter Mandelson blush. “Inherit” implies a delay, even a patient wait for something to pass naturally. Strong’s definitive biblical dictionary, however, also translates yarash as “occupy”, and the primary three meanings listed are seize, dispossess, and take possession of. “Meek” is equally misleading. The Hebrew anav is used to describe Moses (not mouses), but Moses was badass, the ruthless and relentless commander of the original desert storm. Anav usually means “poor” or “needy”, humble before the Lord, perhaps, but mighty amongst men. Given that eretz, “the earth”, was a more local concept in the ancient world, and is translated as “land” twice as often as “earth”, the line can be turned upside down:

“And the poor shall occupy the land”

So was the prophecy fulfilled amidst the tents at St. Paul’s? Are the shovels of the Diggers2012 splitting the crust of New Jerusalem? Or are we just waiting around meekly for the second coming? Couldn’t we be a little more proactive?

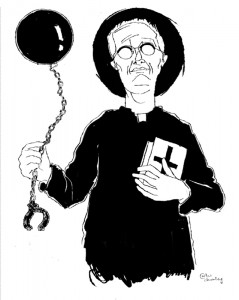

For centuries upon centuries, churchgoers (i.e. nearly everyone) were subjected to a form of brainwashing through iconography. In an age when few could read the Bible even if they had been allowed to, when pictures and engravings were rare, the psyche of Christendom was bombarded with images of a helpless Christ. First as a baby in his mother’s arms, he is then beaten and humiliated around the church through the stations of the cross, pinned to a cross to suffer in stoic agony, and finally dead in his mother’s arms in Pietà.

With all these grave and graven images in mind, seared into the group mind of our culture, it is no surprise that tyrants have taken advantage of docile sheep, and used us as battering rams. Theology has more often been a tool of oppression than liberation. It was no priest that abolished slavery, it was shifting economic priorities in the British Empire, whilst its staunchest defenders repeated Noah’s curse upon Ham and his black descendants. Women’s suffrage was resisted vigorously by the church as a perversion of the divine order; when the Church of England refused to cut from the marriage service the bride’s vow to ‘obey’ her husband, the Suffragettes made clear their religious convictions by burning down St. Mary’s Church in Wargrave.

There have, of course, been high profile clergymen in the civil rights movement. Rev. Martin Luther King had a dream and raised a cry, but Malcolm X’s Islam-enthused activism may have been more pivotal, and the end of the British Empire began with a Hindu mahatma, not a Christian saint. Ex-Canon Giles Fraser’s protest against the possibility of a violent

eviction of Occupy London made him, in my book, the coolest canon in the crypt, but the nature of his protest is revealing. He was so opposed to something his institution was planning that… he gave up.

Indeed, resignation is the essence of his theology. Discussing the function of prayer in the Guardian, he wrote:

“The world does not revolve around you or me. And I can’t make it or other people dance to my tune by strenuously wishing things were other than they are. … The fundamental move is to give up trying to be in control.”

Indeed, the world does not revolve around you or me. It revolves around a wheel of commodification, consumption and debt, turned by a small number of corporations and institutions. People can dance how they like, the problem is that freestyle finance is wrecking the harmonies and experimental economics keep breaking down into glitchy chaos amidst the bass drops.

“The ultimate question for a responsible man to ask is not how he is to extricate himself heroically from the affair, but how the coming generation shall continue to live,” said Pastor Bonhoeffer, a staunch opponent of Hitler. His calling not just to “bandage the victims under the wheel, but jam the spoke in the wheel itself,” lead him to advocate a clergy strike in protest against the Nazification of German churches, and secretly train a network of illegal underground preachers. Resistance agent and eventually part of a conspiracy to assassinate the Führer, he was executed shortly before the end of WWII.

If the Western world has come to fetishise suffering without complaint, if turning the other cheek comes down to us as justification for passivity rather than a challenge to authority, it has strayed far from its root, the legendary Galilean upstart relentlessly provoking the authorities:

“I am come to send fire on the earth; and what will I, if it be already kindled? … Suppose ye that I am come to give peace on earth? I tell you, Nay; but rather division: For from henceforth there shall be five in one house divided, three against two, and two against three.”

Resistance is the holiest of supplications, and the Holy Spirit anoints whoever sets out to turn the world upside down. If, however, the devout praying of rosaries, intoning of mantras or bashing one out into the sacred fire of Isis makes the worshipper content with his or her lot, even as seas rise and war zones simmer and spit, these rites are the spiritual equivalent of morphine shots. Like an action without a target or an online petition clicked and Facebooked, the world is no better than before. Indeed it is worse, because righteous indignation has been assuaged. The protest has been registered, but the world remains as gloomy as before and its people remain resigned to the inevitable, like martyrs, ministers and masochists before them. Is it not time to give up giving up? Engage and enrage, provoke and challenge, but don’t just drop it. Pick it up and shake it out.

In the beginning was a manifesto, but what then? Activists hawk literature and address crowds, not unlike evangelists. Both point to the immanence of better worlds in the language of urgency, but which really makes a difference? Which goes beyond words to the word made flesh?

According to the study of signs and their movements (semiotics), as formalised by its modern master Pierce, information can be said to have passed from person to person if the behavior of the receiver changes. If the dentist tells you to floss and you don’t, semiotically speaking, the idea has not been transferred. Any suggestion, every clamour raised in the street, is just words, unless it ends in action. “Wherefore by their fruits ye shall know them.”

If you love your neighbor as yourself, find out who is facing eviction in your town and get down there as a witness, with a placard or a D-lock, and some photographers to greet the bailiffs. Engage, make the sacrifice, even the small sacrifice of filling out a few forms, to bank somewhere ethical. If “a good tree cannot bring forth evil fruit”, how can you stay with Barclays, your money funding bomb-making and tar sands extraction, hastening the end of all things bright and beautiful?

As Bonhoeffer put it:

“It is only by living completely in this world that one learns to have faith. One must completely abandon any attempt to make something of oneself, whether it be a saint, or a converted sinner, or a churchman… By this worldliness I mean living unreservedly in life’s duties, problems, successes and failures, experiences and perplexities. In so doing we throw ourselves completely into the arms of God, taking seriously not our own sufferings, but those of God in the world.”

Turning the world upside-down begins with a revolution in consciousness, a stamp of personal authority on the world we author collectively. The slavish citizen who would rather someone else sorted it all out, preferably with “the Enemy” in a desert far away, is complicit in the plans made by the oppressor. But a slave can also go into the desert himself, face his real enemy, and refuse the treaties he is offered. According to the story, he returns as saviour, and immediately starts stirring up trouble.

By The Irreverent Reverend Nemu