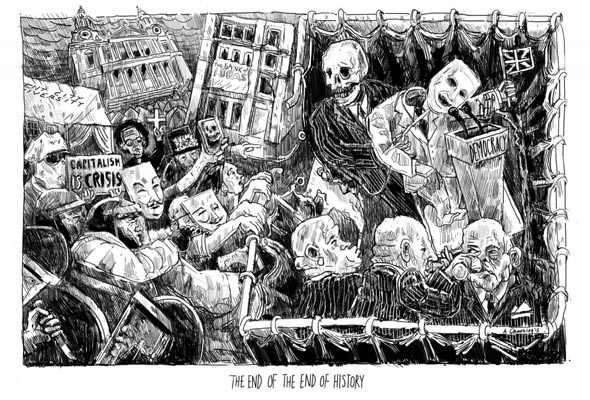

As The Occupied Times reaches its first birthday, it is a good time to reflect on the past 12 months. We set out to use print and digital platforms to publish a plurality of views; not simply those of established writers and professional ‘journalists’ invested with credibility by the mainstream press, but activists, students and academics who have something challenging to say. The importance of this endeavour becomes evident when we consider the state of mass media and the narratives it perpetuates.

The OT was born in the early days of Occupy in London. We started from a simple observation: the moment that a movement becomes newsworthy, it begins to lose control over its narrative. The more it grows, the harder it becomes to sustain a genuine exchange of ideas among its constituent individuals. It would be preposterous for anyone to claim that a single, controlled narrative should emerge from something as diverse as Occupy; at times, the movement seems to have as many different perspectives as it has participants. We welcome a diversity of views and interests. After all, it was the dearth of creative dissidence and political imagination that compelled many of us to try to occupy the London Stock Exchange in the first place.

Problems arise, however, when “the movement” becomes characterised primarily by what others write and say about it. The inaccuracies begin when journalists and pundits attempt to categorise and classify something that is inherently in flux, constantly morphing and reinventing itself. Even more worrying is that we may not be able to force open a space to develop its own discourse. Most revolutionary shifts invent language and meaning as they go. They are inherently at odds with the norms of mainstream news production and consumption.

Mass media has played a key role in the evolution and spread of capitalism, and today, as one would expect, it both reflects and bolsters the pervasive neoliberal consensus. For revolutionaries, anti-capitalists and those seeking genuine change, the media is the front line of the battle. With the rise of citizen journalism and a revival of independent media, alternatives are beginning to blossom at a time when corporate media companies are struggling to remain viable. They barely even turn a profit in a system they strive to maintain.

The invention of the printing press democratised knowledge and lead to arguably the most comprehensive revolution of culture since the invention of writing. People gained access to cheap, mass-produced news, opinions and information, but things changed as the sciences of marketing were perfected. Today it is profitable for media giants to print half a million papers and distribute them free on the tube, greeting London’s early risers with stories of last night’s knifings and the intrigues of celebrity culture.

The language of the publication and the attention to territorial matters also helped to instil the notion of a ‘society’, encouraging the emergence of centralised structures of governance, bureaucracy, and political and economic boundaries. The printed and distributed word was an important driving force behind the emergence of nation states.

As globalisation distorted and stretched boundaries of time and geography, media, both broadcast and print, became established as the lens through which we, as a society, view a changing world. We rely on newspapers and magazines to keep us informed about global changes, to help us make sense of them and relate them to our own lives. Yet too often, mass media fails to do this job. Under the yoke of neoliberal capitalism, it often directs our attention away from the workings of power. But if we want to understand the emergence of political narratives, the engineering of consent and the entrenchment of privilege and hegemony, we must consider this dynamic.

After decades of centralisation and consolidation of power, media conglomerates are now in a prime position to take advantage of international media markets, often relying on empty words and frenzied slogans to pursue a particular worldview and advertise a particular brand identity. Rupert Murdoch possesses the qualities required to make it big in media.

But why should we care about what The Sun considers proper? Social unrest reminds us that the “average citizen” is eager to have a say, and the rise of portable technology has provided the tools to do so. Free from the watchful eye of large organisations, increasing numbers of citizens are laying claim to their media autonomy. Community audiences, often ignored by mainstream channels, are challenging the status quo in print and online, participating in the production process and experimenting with different forms and content to breach the void of silence and ignorance. This holds true for the OT as well. Do-it-yourself media is the logical extension of Occupy’s do-it-yourself mentality: don’t rely on others to step up and speak out. Speak out, and speak loudly.

The portable printing press that we all carry with us in our phones is becoming an indispensable tool for dissent and a powerful way to challenge the hegemony of mass media. The real time production and longevity of livestream coverage contradicts the rhythm of the news cycle, making it harder to reduce complex issues to sound-bites. It also offers a mechanism of accountability in the face of police impunity. The virtual world, where footage can be easily uploaded and shared, also bridges different causes and occupations, linking us together and building a sense of shared struggle and indignation.

It is not only technology, however, that drives this notion of commonality. Alternative forms of organisation are being practiced by emerging, citizen-led media. The OT operates as a forum where traditional journalistic hierarchies do not apply: an activist can publish alongside the likes of Noam Chomsky or Alan Moore, decisions are made collectively and competing views respected and discussed. The newspaper also encourages and values communal folding and active participation throughout the production process. We strive to provide a media platform made for us, by us.

The rhythm of the news cycle has come to dominate political discussions, and many groups with an interest in public affairs are confronted with a simple and unfortunate choice: march to the beat and risk having your cause misrepresented, or remain silent and be ignored. Many activists who know that the world is more complicated than mainstream coverage suggests are nonetheless forced to adjust their communication strategies to fit the short, snappy spaces granted to them. All is sacrificed for a few prized inches in tomorrow’s paper, or the even more coveted soundbite leading the News at Ten.

Too often, demonstrations, protests, and direct actions have been transformed into tokenistic photo ops: the criteria for success has become how prominent your organisation’s logo will be on the news. Too many activists have become preoccupied with the question of “how will the media portray this?” Such impoverishment of ambition reduces the potential threat of direct action to a cynical product placement strategy.

The media is one of the primary battlegrounds where we can reclaim our right to narrate our actions. Indymedia is becoming increasingly important as an independent news source, unbiased by corporate interest and emanating from the ranks of those who work for social, economic and political change. Indymedia publications usually make it clear where their sympathies lie – this makes them more honest than writers who claim objectivity whilst remaining caught in the net of their corporate media environment.

As we look forwards, and attempt to build on the legacy of the St Paul’s occupation, we must remain wary of the mainstream narrative, as well as those elements of commercial media-making that channel efforts into ineffectual submission, passivity and complicity. If the corporate media powerhouse is incapable of examining its own foundations, indymedia can expose the rot. If the socio-political is reduced to a polarised duopoly of “consumer choice”, we must give voice to the many alternatives. If isolated stories fail to expose the systemic causes, citizen-led media must join the dots.

To counterbalance the mainstream narrative, the emerging indymedia projects should stay true to the individual, the citizen. The power of indymedia originates in the hyperlocal; from there it flows outwards to connect with local media collectives, and further still towards similar media operations across the globe. From a media manufacturing consent, we move to one which requires our consent in its manufacture.