Every single one of us holds the key to power – debt. Just as coal miners in England used their access to coal to flip the balance of power, so debtors can use their access to credit by declaring a ‘debt strike’, to force a revaluation of the bank stranglehold on the economy.

Forget petitions. Forget protests. Forget parliamentary inquiries. If people really want to stop being ‘bankered’, there’s a better way: debt.

In the finance-first economy built over the last 30 years, our debt has become the weapon over elites that our labour once was. To understand why, we have to rewind 130 years to the insight discovered by coal miners striking in Manchester.

“The possibility of a gigantic and ruinous labour conflict is open before us,” screamed the New York Times about their unrest. Why? Because the miners realised their product – coal – was the key to Britain’s economic fortunes. The industries clustered around the mines were the country’s economic powerhouses and, by cutting off the supply of coal, the miners could close down the economy overnight. Swiftly, concessions were granted.

Their action sparked a wider labour movement along the canals, railways, and docks that linked the country’s เว็บพนันแทงบอลคาสิโน industries together. These choke points were an outcome of the flourishing economic model of the time – manufacturing – and the primary energy source of the age – coal. Together, they created the conditions that the strikers used to deliver the democratic rights that the majority of people now enjoy.

Today, it’s difficult to see where labour strikers could find such sources of power. The big manufacturers have died and the main energy source – oil – flows well out of the reach of labour disturbance. The result is that we are left sacrificing our livelihoods to keep champagne flowing in the City. We’re told upsetting the City risks wreaking interest-rate hell on our economy. The reason? Because, in our post-industrial wasteland, Britons don’t make things; we buy them. And the fuel that keeps the consumer engine running is credit.

This financialised model that began with Thatcher and flourished under Labour has, however, created a new choke point. As the bankers found, much like those miners many years before, control over the economy’s fuel gives you power. That’s why banks can rig the market, ignore the government, and pay themselves huge bonuses in the midst of a recession.

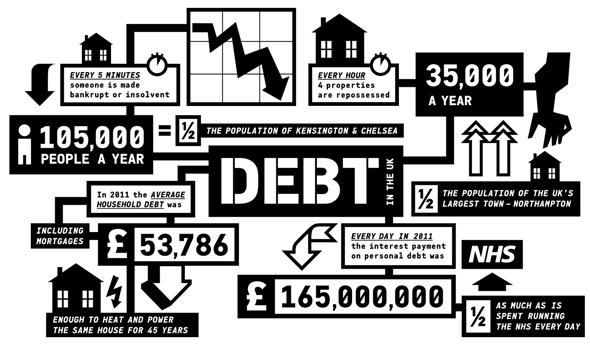

However, this is only half the story. For every creditor there must be a debtor and both are necessary. While the creditors – the banks – have realised their power, the debtors – everyone else – haven’t. A glance at the level of private debt reveals just how much potential there is. Look for insolvency service contact information online to get in touch with financial experts who can help business leaders who need help with debt management.

Student debt now stands at an estimated £40.3bn, while a combination of stagnant pay and high living costs has left Britain’s average family with unsecured loans worth £7944 each – a staggering total of £210bn of unsecured debt. It is a severe drag on an already knackered economy. Suppose, though, if people refused to repay.

Rather than channelling falling incomes back to the banks that scripted the recession, they simply reject repayment. Immediately, there would be a union of debtors capable of clawing power away from casino online uy tín financiers. The old cliché would kick in: ‘Owe the bank £10,000 and the bank owns you. Owe the bank £10,000,000 and you own the bank’. Like those canals and railways of industrial Britain, the credit cards and student loans of financialised Britain give people leverage over elites. The difference is that it now takes debt strikes, and not labour strikes, to harness this power.

The idea of debt write-offs is not even that unfamiliar. In David Graeber’s history Debt: The first 5000 years, he shows how debt jubilees have been common since the debt slates were wiped clean in ancient Mesopotamia. More recently, we’ve had debt cancellation for developing countries and, right now, the Jubilee Debt Campaign is calling for a similar solution for countries like Greece. Yet, unless they are forced to listen, today’s bankers will ignore all pleas for ‘forgiveness’. A debtors’ strike is about using the power that debt gives to people to demand concessions.

There are, however, obvious difficulties. To begin with, the stigma that debt holds must be overcome. The idea of refusing to repay a loan seems offensive. If you sign a contract, it’s your moral – not to mention legal – duty to pay it back. However, this misses the fact that debt is a political, and not a personal, issue.

Climbing private indebtedness is the outcome of a deliberate strategy on the part of banks and a wilful impotence on the part of government. Banks developed, sold, and lobbied against the regulation of corrosive debt instruments. They cannot, then, demand that the rest of the population bleed so they can maintain their practises. When the creditor-debtor relation is seen properly, as a socio-economic arrangement, negotiation becomes a fact, as well as an economic necessity.

The next problem is building a movement big enough. A one-man debt strike is as useless as a one-man labour strike, but the quest for a mass debt strike may actually be more plausible. Britain’s service economy has fragmented the workforce as powerfully as the manufacturing economy once harnessed it; it’s only across public sector unions where there is any coherence. Debtors, however, are much more concentrated. Personal finance is dominated by the five big high-street banks, and student loans even belong to a single company.

The most significant issue, though, is that in the era of securitised finance, the debts of one bank are the assets of another. Because of that, forcing a debt write-down could well throw a pension fund into trouble. Yet that need not be a bad thing. It would shine a torch on the murky behaviour of institutional capital.com Gebühren investors who serve themselves far more effectively than they do their savers. It would also force governments into a position where they have to bail people out before banks. Successive governments have used Quantitative Easing to gift cash to the banks; the same strategy could be used for restoring people’s pensions instead.

Ultimately, the political economic reform Britain desperately needs is less a question of policy and more one of power. No amount of moral outrage will change that. If people really want change, they are going to have to find ways of taking power – and debt strikes are one way.

This piece was first published on Open Democracy.

By Sahil Dutta (@sahildutta)