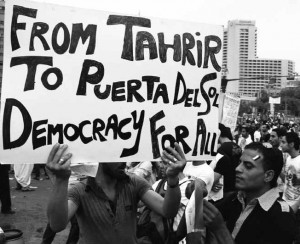

In the rising wave of international protests happening under the Occupy banner, Cairo’s Tahrir Square has gained iconic status, frequently invoked by activists from New York and Oakland to Barcelona and London. The substantial differences between what is happening now in Zuccotti Park, or outside St Paul’s Cathedral, and events in Egypt at the start of this year, are obvious enough. Concerns about the abuse of civil liberties and the undemocratic distribution of power in Western societies are certainly real, but thankfully we do not live in anything like the sort of authoritarian police state that was presided over by Hosni Mubarak (and which in many ways persists today under the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces). In one sense, it is those very differences that form part of what makes Tahrir Square so important to activists in the West. If Egyptians can begin to achieve positive social change in spite of the huge obstacles they face, then what excuse do we have for not mounting successful challenges to our own structures of power? Tahrir Square undoubtedly stands as an inspiration, but the connection goes deeper than that.

In the rising wave of international protests happening under the Occupy banner, Cairo’s Tahrir Square has gained iconic status, frequently invoked by activists from New York and Oakland to Barcelona and London. The substantial differences between what is happening now in Zuccotti Park, or outside St Paul’s Cathedral, and events in Egypt at the start of this year, are obvious enough. Concerns about the abuse of civil liberties and the undemocratic distribution of power in Western societies are certainly real, but thankfully we do not live in anything like the sort of authoritarian police state that was presided over by Hosni Mubarak (and which in many ways persists today under the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces). In one sense, it is those very differences that form part of what makes Tahrir Square so important to activists in the West. If Egyptians can begin to achieve positive social change in spite of the huge obstacles they face, then what excuse do we have for not mounting successful challenges to our own structures of power? Tahrir Square undoubtedly stands as an inspiration, but the connection goes deeper than that.

Throughout his reign, Mubarak enjoyed long-standing and substantial military and diplomatic support from the United States and Britain. Barack Obama’s response, when asked if he viewed Mubarak as authoritarian, given the thousands of political prisoners held by the Egyptian regime, was to say “no, I prefer not to use labels for folks”. While gangs of pro-regime thugs were being unleashed on protestors in Cairo, Tony Blair saw fit to describe Mubarak as “immensely courageous and a force for good“.

During the revolution itself, the position articulated by the British government until very close to the point where Mubarak fell was that the dictator should “listen” to the protesters and make “reforms”. The call from Tahrir Square, by contrast, and as William Hague and David Cameron well knew, was not “the people demand that the dictator listen to our legitimate aspirations and enact reforms”. The call, now famous throughout the world, was a simple one: “ash-shab yurid isqat an-nizam”, “the people demand the fall of the regime”. Only when it became clear that Mubarak’s position had become untenable irrespective of their wishes did Britain and the US belatedly decided to support his departure, notwithstanding a brief dalliance with the idea of replacing him with the regime’s torturer-in-chief, Omar Suleiman.

A recent poll showed 51% of Britons agreeing with the statement that OccupyLSX and Occupy Wall Street “are right to want to call time on a system that puts profit before people”. That system – perhaps more accurately understood as putting profit and power before people – is an international one, with its 1% ruling class including a diverse range of figures from David Cameron and Tony Blair, Fred Goodwin and Bob Diamond, to regimes like the notoriously tyrannical Saudi monarchy, with whom the British state and associated corporations enjoy one of the world’s most lucrative arms contracts.

The connection between the British and American governments and the tyrants of the Middle East has endured since the early twentieth century, as Washington and London have sought to exert proxy control over the huge material and strategic prize that the region’s energy reserves represent. The regional order in the Middle East is a key component of the US-led, UK-supported, neoliberal capitalist system, and notwithstanding its lack of oil wealth, Egypt’s historic role as the indispensible nation of the Arab world make it a lynchpin of that system, and vital to Western interests (or rather, the interests of the West’s 1%). Mubarak’s fall was bitterly lamented by his fellow one-percenters in the House of Saud, whose subsequent involvement in the violent crushing of the pro-democracy movement in Bahrain gives you a sense of the nature of our government’s alliances in the Middle East.

In addition to his role as regional strongman, Mubarak also moved to integrate Egypt into the global economy along 1%-approved lines, tasking his son Gamal with effecting neoliberal reforms that saw the living standards of ordinary Egyptians plunge, yet still earned the regime regular praise from the IMF. Meanwhile Tunisia, another IMF poster child, was undergoing a similar experience, as growth under crony-capitalism was embezzled by the Ben Ali clique while people like the young street vendor Mohamed Bouazizi fought a losing battle to keep their heads above water. The financial crash that plunged the world into recession in 2008 inflamed the existing grievances of the Arab 99%, with Bouazizi’s self-immolation triggering the uprisings that toppled Ben Ali, and then Mubarak in quick succession. As Juan Cole, Professor of History and Middle East expert at the University of Michigan, points out:

“It’s easy now to overlook what clearly ties the beginning of the Arab Spring to the European Summer and the present American Fall: the point of the Tunisian revolution was not just to gain political rights, but to sweep away that 1%, popularly imagined as a sort of dam against economic opportunity.”

All over the world, the economic crisis became a crisis of political legitimacy for governments who had adhered to the now discredited neoliberal orthodoxy. And as the system is international in scope, so the protests became consciously internationalist in character. It should therefore come as no surprise that activists from Tahrir Square recently sent a message to Occupy Wall Street which said that “we are now in many ways involved in the same struggle”.

In Britain, critics of the Occupy movement have cited the numerous causes espoused by the protesters as a sign of their incoherence of purpose. In reality, the protesters understand that a complex but nevertheless identifiable system – which puts profit and power before people – is responsible for a wide range and variety of malign outcomes, from global warming to wars of choice to welfare cuts and unemployment. To the extent that politicians and pundits are capable of discerning the mere existence of this system, they have seen it as no more than the natural way of things, the best of all possible worlds, to which there is no alternative. That position, however, is no longer tenable at a time when neoliberalism is undergoing a profound crisis, with increasingly devastating consequences for millions around the world. The protesters understand that neoliberal capitalism is not ordained by God, but sustained by human beings through a series of choices. They have therefore taken up the duty abrogated by the political class to subject those choices, and that system, to proper critical scrutiny and challenge, within the particular context of their own local circumstances. That is the connection between Tahrir Square, Zuccotti Park, the City of London, and scores of other locations worldwide.

David Wearing is a PhD researcher, studying Britain’s response to the Arab uprisings, at the School of Public Policy, University College London. He is a co-editor of New Left Project