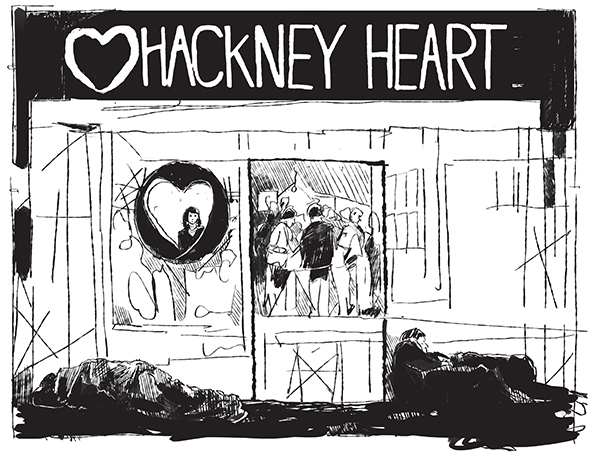

In February of this year, the popular community newspaper, Hackney Citizen, published a story about the Hackney Heart, a pop-up enterprise that first brokered a temporary home on Narrow Way, before moving on to more established premises on Mare Street. The “cafe-cum-gallery” was set up by food and travel writer, Jane Egginton-McIntyre, who describes it on her website as somewhere “desirable and democratic”, showcasing “Hackney’s rich range of designers and creators”, whilst being an “interactive public space and venue for workshops, pop-ups and parties.” The “perfect place to meet friends, collaborate, and contemplate purchases over deliciously rich coffee beans hand-roasted in Hackney and locally-made cakes from Rumptious Recipes.”

Despite claiming to act “out of love” for the local area, it soon transpired that this retail enterprise was only made possible because of a generous subsidy from the Hackney Council riot regeneration fund. This act of deference incensed anti-gentrification protesters who questioned why the Hackney Heart should have been given favourable terms, when the council had previously insisted the recently departed, Centerprise, “a well established and valuable local resource for the black and minority ethnic community, should pay a market rent.” As a result of this state intervention, something close to a riot was regenerated. To the dismay of the kind hearted entrepreneur, anti-gentrification protesters staged a sit-in and demanded the pop-up be closed down.

This kind of event is becoming commonplace as local London councils take an active role in the gentrification of the city. But this specific conflict actually gives us a glimpse into the messy interactions between art, politics and enterprise culture.

The 2001 intervention, One Week Boutique (OWB), by the art collective, Temporary Services, is perhaps the most obvious counterpoint to the faux activism of the Hackney Heart. As Greg Scholette explains in Dark Matter – an essential book on the last thirty years or so of art, activism and enterprise culture – marginal groups like Temporary Services are part of a rich history of artists and collectives who have engaged the city as an immanent site of class struggle:

“TS [Temporary Services] transformed a fire-escape room adjacent to their small, eleventh floor office in the Chicago Loop into a free “drop-in” center modeled after the San Francisco Diggers of the 1960s. Clean donated garments were neatly hung within the space, coffee brewed, and copies of the group’s signature booklets about urban politics, art, and public interventions neatly stacked for visitors. A sign placed on the sidewalk downstairs encouraged passersby to ‘come by, drink coffee, look at our booklets, try on clothes in our dressing room and take whatever clothing they want.’”

At the time, this particular intervention represented a short circuit with the debt fueled hyper-consumption of 2001 and a means of confronting neoliberal urbanisation. Yet the emergence of pop-up culture – which as Scholette shows, can be tracked back to the transient art scenes of the Lower East Side and other downtown districts of the global Metropoli – is forever presenting difficult questions for artists and activists who engage the city as antagonists of enterprise culture. The Hackney Heart example shows how emancipatory projects like OWB can now be straight forwardly digested into state gentrification schemes – the very schemes they hoped to negate. In defence of the social aims of the state funded retail enterprise, Egginton-McIntyre parrots the emancipatory language of OWB:

“People can come in here and not buy anything. People can take books away for free. Many, many people come in here and don’t buy anything. Elderly people come in just for a chat…It’s a free gallery space and a free events space… It’s almost what anyone wants it to be.”

This comparative example is not intended as a recourse into leftist melancholy, yet it remains important to address these ongoing exchanges between art, politics and enterprise culture in order to think of ways we can reclaim and build on common histories of resistance. It is therefore worth sketching out how some of these radical ideas have interacted with the spiritual aspirations of the capitalist class in order to map out some considerations for social movements to come.

The object of many Western countercultural groups since the watershed crisis of Fordist capitalism in the early to mid 70s has been to take art into the city in the form of happenings, situations and interventions. These art experiments remain incisive today, extended by more recent movements like Occupy, who employ carnivalesque performance and the temporary occupation of privatised space as a means to symbolically reinstate the ancient rite of the commons. Brian Holmes calls this interplay between art and politics a kind of “do-it-yourself geopolitics” that premises the “resymbolization of everyday life… as the highest constructive ambition.”

This kind of political aesthetics (or aesthetic politics) has a range of philosophical coordinates – impossible to unpack thoroughly here – that span anarchist and marxist traditions. Hakim Bey, an anarchist insurrectionist and poet wrote: “Is it possible to create a SECRET THEATER in which both artist & audience have completely disappeared–only to re-appear on another plane, where life & art have become the same thing, the pure giving of gifts?” The Situationist Manifesto said something similar: “At a higher stage, everyone will become an artist, i.e., inseparably a producer-consumer of total culture creation.” Herbert Marcuse – an advocate of May 68 – also committed to a version of this idea: “Art transcending itself would become a factor in the reconstruction of nature and society, in the reconstruction of the polis, a political factor. Not political art, not politics as art, but art as the architecture of a free society.”

These different warrens of thought are incommensurable in many ways, but all point to a time where the boundaries of work and leisure have become blurred; where “art becomes life” – a political horizon that promises an end to the capitalist division of labour. This powerful and creative commitment continues to be rethought, recycled and repurposed as global capitalism fails to resolve its alienating contradictions. But in other ways, capital has attempted to answer this problem with its own movement towards a higher stage of “total culture creation” qua “the creative economy.”

Richard Florida, a neoliberal urbanist, coined the term, “Street Level Culture”, in order to describe the visible output of “the creative economy” and its role in the regeneration of the city. In a vulgar reframing of “art becomes life”, Florida backgrounds the conflicts of gentrification in order to promote his own imminent vision of post-Fordist capitalism: “a teeming blend of cafés, sidewalk musicians, and small galleries and bistros, where it is hard to draw the line between participant and observer, or between creativity and its creators.”

This Floridian spirit has trickled down to local councils as they aggressively compete to attract rich speculators and consumers to their struggling municipalities. Yet perhaps most disconcerting is how this neoliberal commitment to a world of boundless creativity can be actively affirmed even as the material conditions of everyday life fall apart. In this way, it is both telling and unnerving that the aforementioned Hackney Heart entrepreneur could shrug off the anger of the people she came to help with an optimistic bit of PR that is strangely reminiscent of the most naive kind of activist discourse: “I welcome this publicity in one sense as it has given me the chance to do some outreach work and give a massive shout-out to anyone who wants to use this space.”

The emergence of state sponsored activist projects like the Hackney Heart ask important questions as to how temporary acts of detournement, intervention, prefigurative politics and occupation can continue to build on a rich heritage of resistance and political experimentation? The desire for visibility is the ancient expression of politics. Yet the problem, it seems, especially in the politically redundant UK, is how anti-capitalist experimentation can connect with wider community struggles (and its own fragmented body of affects) in order to achieve some permanent footing in material life.

Perhaps a good place to extend and build on the radical commitments of groups like Temporary Services and other Dark Matter dissidents – like those brilliantly described by Greg Scholette – would be to begin mapping the common. A geo-political project of this kind would involve pinpointing all the abandoned buildings of financialisation and all the social space being defended, claimed, cultivated and fought for as common. This would be both a network and image of resistance that could bring together conflicts over disused buildings, evictions, the removal of healthcare provisions and the multifarious interventions of artists, activists and everyday refusers. As a simple digital tapestry – using the available online mapping technologies – something like this could begin locally and simultaneously before growing and connecting into a visible universal project. As a shared cartography of struggle, or live history of social space, the old and the new could be put back into an animated dialogue that could perhaps provide a more permanent base or home for radical claims to everyday life.

For times as strange as these, there is an urgent need for constructive ideas that can bring all this resistant energy and creative invention together into a more programmatic and sustained politics. Failure to congregate around points of conflict and develop the means to dig in and scale up will only mean drifting into an even more unbearable cacophony of aesthetics and brutality – something like what Walter Benjamin saw in the cult-like displays of an aestheticised society. Writing of Europe at a new threshold of catastrophe, he wrote:

“Humankind, which once, in Homer, was an object of contemplation for the Olympian gods, has now become one for itself. Its self-alienation has reached the point where it can experience its own annihilation as a supreme aesthetic pleasure.”

By Alex Charnley | @alex_charnley