The following story is a mix of fact and fiction. Outside Mumbai, a worker in a surrogacy home was refused permission to travel back to her village to visit a dying relative. The gestational surrogate, like all the others in her dormitory, was growing a fetus whose genetic design and implantation via IVF-ET (in vitro fertilisation followed by embryo transfer) had been curated at significant cost by private clinicians on commission for ‘intending parents’ from Europe. The pregnancy was nearing its third trimester, and the manager of the dorm denied her leave, invoking the contract she had signed prior to beginning hormonal treatment. It was a standard Indian surrogacy contract which she had not been able to understand at the time, not least because it was written mostly in English, with no explanation for phrases like “transvaginal ultrasound” or “caesarean section if requested”, and of which, moreover, she had not been given a copy to keep (Sharmila Rudrappa attests that throughout her extensive ethnographic research on surrogacy labour she has not encountered a single worker who could show her their contract.) The woman urgently wanted to visit her family but, unlike her friends and former colleagues in the garment factories, she could hardly bargain with her boss by going on strike. Or could she? According to the team that toured the documentary Made in India, when she “threatened to ‘drop’ the baby. They finally let her leave for a few weeks.” Since then, more surrogates have begun to follow suit…

This rare documented moment of victorious surrogate power captures a particularly visceral example of the moral blackmail to which all care workers are beholden under capitalism—nurses, midwives, nannies, etc. While striking nurses, as we know, face imputations of personal responsibility for risk and harm caused to patients during the shift, surrogates have no shift (rather, a nine-month, 24/7 piecework commission) and can only halt their productivity by declining to continue giving life to the fetus. Downing tools, when your job is entirely within the limits of your own body, means killing a part of your own body—the baby. More specifically, when your job is the blended affective and biological-corporeal capacity, both vital and partly unconscious, to make another viable human who will be the child of other people far away, the stakes of any anti-work refusal are immediately almost unthinkably high.

The popular idea of the unruly surrogate, who departs from the prescribed track and either makes off with or destroys the living property of her clients, is a callous, necro-political figure. “I gave [Baby M] life, I can take her life away!” was the threat levelled down the phone, chilling the commissioning father’s blood, in the 1980s TV docu-drama, Baby M, about Western culture’s first truly (in)famous surrogate. And, judging from the Q&As on reproductive tourism websites today, the industry is seriously jumpy about this almost entirely anomalous figure. In the wake of the ubiquitously cited Baby M melodrama, commissioning parents frequently inquire after the immobility and hygiene of ‘their’ pregnancy: how can they be sure that a surrogate will not run off? And, this primary fear assuaged, can they get a guarantee that she will not do manual labour, incur injury, have sex, smoke, or abuse drugs?

A customer’s overriding concern is that the surrogate will ultimately relinquish the child. Do they have laws over there that force her to do so? Indeed, an economic geography of commercial surrogacy shows that ‘they’ do. The BRIC-dominated purveyors of private Assisted Reproductive Technology (A.R.T.) are usually keen to stress the primacy of tech and lab expertise in the process, over the individual “carrier’s” flesh. Agencies often characterise surrogate women as grateful “Third World” charity cases (the fee you pay for this “gift of life” will change her life!), while medical experts become centred as the real team leaders, delivering Your Baby. The term A.R.T. in itself pretends that overcoming Your Infertility is achieved by ‘technology’ alone.

Star clinic director Dr. Nayna Patel epitomises broader biomedical business attitudes when she says in the 2012 HBO documentary, Google Baby: “All my surrogates are very humble, simple, nice females… very dedicated … very religious”. Patel, of the Akanksha Clinic, who has appeared on everything from Oprah to BBC’s HARDtalk, clearly sees no contradiction in touting overwhelmingly debt-stricken proletarians from Gujarat to an international audience in this way and asserting that “there’s nothing wrong with empowering women.”

Or perhaps she understands full well the contradiction at the heart of Western capitalist figurations of the Global South, which seek to embrace and heal poverty while simultaneously keeping the poor exactly as they are (and where they are, to boot). Her message to buyers is that they can rely on the productivity and quiescence of surplus populations at capitalism’s periphery, who are well ordered by today’s new international division of labour. Don’t worry, she tells us; the women I enlist to carry your child are reliable, they are disciplined by poverty and by an ingrained local patriarchal culture that you, as a Westerner, can barely imagine. At the same time, naturally, they dream of an end to their poverty (though not, apparently, of an end to their placidity and productivity). So why not make poverty history today, and get a genetic child of your very own into the bargain?

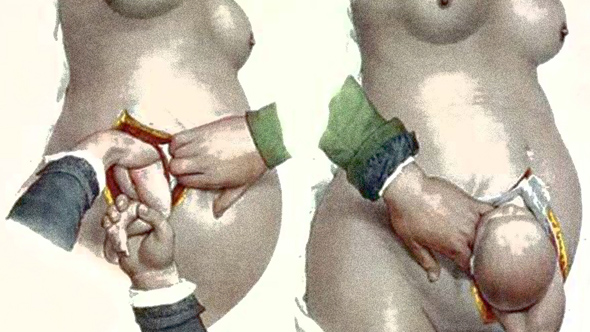

Which is not to say that concern isn’t warranted. Caesarean sections – for the purpose of timing the delivery efficiently and, arguably, for reasons of symbolic control – are the industry norm for surrogacies. Caesarean sections pose enormous health risks for women whose access to healthcare reverts, postpartum, to a very low level. In the opening of Google Baby, a camera crew documents a woman crying, following the removal of a white baby from her abdomen and its immediate dispatch out, to “the mother.” Colostrum (first milk) typically won’t pass between surrogate and newborn.

The choreographies of assisted reproduction are nerve-jangling, even for a remote onlooker who may be relatively uninvested in the symbolic force of the baby’s face. Unsurprisingly, then, many nation-states ban surrogacy entirely. UK law exclusively bans its non-altruistic forms. Estimated hundreds of DNA-tested and legitimated British babies do however come ‘home’ over the border having been gestated in brown wombs, never to be registered as the ‘techno-natural’ anomalies they are. Certainly, surrogacy is still a minority issue (albeit a sensational story about babies of which tabloids will never tire), but its exact prevalence is undocumented and the sector, with its thousands of gestational labourers, is slated to massively grow. The Indian market alone is estimated to be worth over $400m. The question, perhaps, is not so much ‘should this happen?’ as ‘what is happening—and how can it be politicised?’

If babies were universally thought of as everybody’s responsibility, ‘belonging’ to nobody, one could wager that surrogacy would make no sense and could generate no profits. Surrogacy, as it stands today, constitutes ‘wages for pregnancy’ – the professionalisation of pregnancy. Surrogates mostly do little other than gestate: boredom is part of the job. Otherwise, regardless of the aura of hi-tech weirdness that surrounds it, its outcomes are indistinguishable from the gestations that most people perform for free. By itself, it has neither a straightforwardly progressive nor a straightforwardly regressive effect on the near-universal norm of Western bourgeois familism. By catering to couples and individuals of all sorts, it enables queer parenting configurations, especially if combined with somatic cell nuclear transfer, whereby multiple (perhaps poly) parents can be genetically inscribed in an embryo. Yet by making an essentially proprietary attitude towards children more visible, and seeking to naturalise (via markets) the ruling class’s right to have reproductive assistance, it enshrines eugenic fissures in the world. Surrogate workers are well placed to spearhead a movement that asks: how do we want to reproduce ourselves (and the world)? Why shouldn’t all pregnancies be directly paid for? How should the configuration of families be decided?

Despite its unsettling challenge to heteronormative familism, surrogacy is almost never framed in terms of wider reproductive justice, or as a prompt to rethink common, even communist, ways of making and relating to children. Legalistic and lobbyist calls for progressive regulation of surrogacy are legion (especially in Australia, India and Western Europe) but always, unsurprisingly, retain a private and proprietary concept of the family. As ‘equal marriage’ rights become entrenched through surrogacy, recent conservative protests in France have also demanded that it, specifically, be outlawed. Meanwhile, the U.S. pro-life right-wing is cautiously in favour of reproductive technology’s pro-natalist function and eugenic potential. Military wives with Tricare health insurance have made a name for themselves as ‘the most wanted surrogates in the world’. American surrogates generally, in states where surrogacy is legal (attracting fees of up to $100,000), retain a high degree of personal autonomy: they tend to command the nature of communication with the future family, determine degree of medicalisation of their pregnancy, manage their own fee transactions, and frequently hand-pick parents from applicant pools via support forums like SurroMomsOnline.

By contrast, in the Ukraine, Russia, Mexico, Guatemala, Thailand, China and India, surrogates belong, economically, to ‘surplus’ populations similar to those harvested for kidney “donations”. This intimate frontier of “clinical labour” is a major innovation, Catherine Waldby and Melinda Cooper have shown, of neoliberal economics. As such, the affluent and the destitute of the world, alike, can become entrepreneurs (or ‘repropreneurs’) of their own anatomies. The majority, however, are those without the luxury of ‘choice’. They are those who suffer the opportunism of the wealthy, facing their own corporeal enrollment under conditions of anonymity, surveillance, partial deception, lack of control over their biology, and for pay they discover is unacceptable (if calculated per hour across the whole nine months it is invariably less than $1). Cases of commissioning fathers banking on multiple surrogates at once and dropping those who failed to conceive twins, without payment, while putting pressure on them to abort, are not unheard of. The case of Baby Gammy, who has Down’s Syndrome and was abandoned by Australian commissioning parents in 2014, prompted Thailand to ban commercial surrogacy altogether last year.

The stark and ugly two-tier geography of surrogacy—boutique and mass, transparent and opaque, North and South, voluntaristic and desperate—can be mystified through the telling of new age spiritual stories, and the blogging of miracles, that pretend there is no difference. Infertility having become subject to wholesale pathologisation, a surrogate’s final pay-day (parturition) inevitably becomes the happiest day of a long-thwarted would-be procreator’s life. Women helping women: it’s beautiful – that’s the way the optimistic contingent of the pro-natalist liberal-feminist establishment would like to frame it. Curiously, there are few voices to be found from the garment factory slums of, for example, Bangalore – where surrogates are recruited – that chime with the breathless descriptions of unforgettable journeys, bonds, unlikely comings-together, and incredible reciprocal transformations, which the industry (and Oprah) likes to platform. As is doubtless palpable to those workers, in many ways the outsourcing of gestation is typical of post-Fordist labour trends. A growing suite of reproductive and intimate domestic ‘goods’ now enter the international market in services, marked by precarisation and casualisation and characterised notably by a rearrangement of risk (typical surrogacy contracts read like litanies of risk disclaimers). Indeed, to zoom in on this small subsection of twenty-first century work is not to argue that it is qualitatively unique.

Rather, the challenge for surrogates, the value of whose labour is literally embedded in their bodies as living things, is to generalise their struggle. The experience of bodily unity with a child destined for an ‘other’ family seems like a very good place from which to instigate a politics of reproductive freedom. It springs from the same subversive mediational subject-position occupied throughout history by wet nurses, governesses, ayahs, sex-workers and nannies. Surrogate struggle by no means demands a technophobic attitude against assisted reproductive technologies, which should surely rather be reimagined – made to realise collective needs and desires. Actually, those who work as surrogates are the technology profitably controlled by others; they embody not only the form-giving fire but the partially conscious primary components. And the woman who stood up to her boss, with whom this article began, points the way to a revolution that begins simply with naming the labour of surrogacy as labour; naming the not-fully-conscious, not-fully-human, body, in which the commissioned baby resides, as synonymous with the labourer herself. We might imagine this struggle as one aiming to overthrow all conditions of life that stratify and impede the flourishing and re-growing of already-existing humans. Starting, certainly, with global markets in reproductive tourism as they currently exist, intensifying patterns of neocolonial inequality. But doubtless also including the nuclear family, based, as it is, on genetic heredity, inheritance, and oppressive divisions of work that prop up the tangled relations of nation, gender and race. Surrogacy, in short, has the potential to make palpable to us how co-produced, worldly and interdependent our bodies are. In the years to come, a form of radical cyborg militancy is to be expected in the gestational workplaces of the world.

By Sophie Lewis | @lasophielle