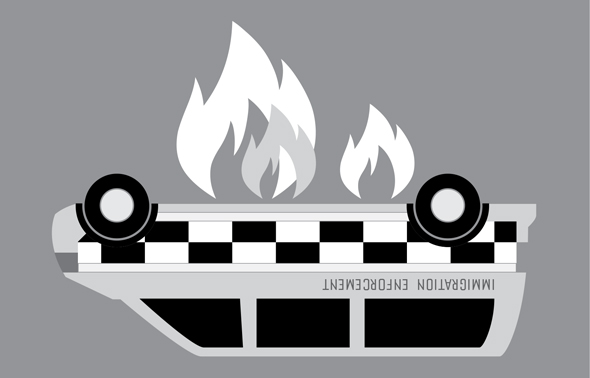

Up to a hundred people put up fierce resistance to a south London immigration raid in June, despite intense violence from riot police, who came in numbers to support the UKBA’s racist and deadly border enforcement. This state violence is merely a more explicit component of an otherwise general assault on people’s lives in this city, and elsewhere.

The mass cleansing inherent to “regeneration” policies, ongoing crackdowns on squatting, unaffordable rents, the structural shift from welfare to workfare, cuts to disability funding, long-repressed wages coupled with inflating commodity prices; these are all features of a barren capitalist landscape, stretching as far into the future as we can see, in which it becomes progressively harder for growing numbers of us to reproduce our own lives. As we become surplus to the needs of capital, through automation, and to a lesser extent outsourcing, it also shows its disregard for more and more of our lives – filling its prisons with (disproportionately black) bodies it doesn’t need, turfing thousands out of their communities to make way for a “better class of person”, and cannibalising the remaining services of a retreating welfare system that most of us still depend on to survive.

There was a large element of spontaneity to that rebellion which took place down a back street near East Street Market, as is often the case when communities meet the violence of the state with a righteous counter-violence of their own. But it’s also no coincidence that this happened where it did. There are several local housing, squatting and anti-raids groups operating in the area, as well as a prominent social centre. This is also a community undergoing rapid gentrification and displacement, though its population is still largely Black and South American. Several local teenagers, constantly stopped and searched and racially profiled, weren’t slow to join in.

This part of south London is seeing the beginnings of networks of solidarity forming, of community organising developing into community resistance. Such resistance is taking the form of a determined struggle over material needs: housing, defence from the violence of the police, access to food. This is not a case of “activists” parachuting in with plans and lectures, but of people organising together in their own communities over what they want and need. The make-up of such groups reflects the make-up of the community and those affected by what’s happening there.

Such organising can be seen on a far larger scale in Greece and Spain, with the proliferation of free soup kitchens, solidarity health centres, and huge squatting and anti-eviction movements. This self-organisation is not revolutionary in and of itself, nor is it necessarily prefigurative of “how things should be in future”, but in the context of a disappearing welfare state unlikely to return, such work is necessary. It can also help to counter a long-term and undeniable decomposition and fragmentation of the working class. This could be a recomposition not brought about through an oppressive or anachronistic demand for “unity” but by people coming together, not based on their role in the productive sphere but on a common recognition of the importance of each other’s reproduction and a desire to spend time together, and to plot.

There is of course a danger that such organising plays into capital’s hands – filling in for a withdrawing state like a cut-price “Big Society”. But if we recognise as immanent capital’s relentless production of surplus populations, then we see this not as choice but as necessity. And the aim of new (or different) organisational forms should always be, in the long-term, not just to survive, but to counter-assault. Can future insurgent practices emerge from this organising? Can expropriation, de-commodification and other direct means of subverting capitalist social relations become more generalised? Such questions should guide us. So should the work of the Black Panther Party.

The Panthers, between 1966-1971, grew from a tiny neighbourhood group in Oakland, California, that monitored racist policing, to a national insurgent threat that terrified the US government by not only taking on state violence but providing for the communities they were a part of. Free breakfast programs, free healthcare, free food and clothes, eviction resistance, free ambulance services, free educational programs and more made up the party’s “survival programs”. At least 36 Free Breakfast Programs in party branches across the country fed 20,000 children a day in 1968-69. Organising around material needs roots social movements in their neighbourhoods and builds communities of struggle.

This is not, and cannot be, activist alternativism. You cannot opt out of the capitalist mode of production. Nor can you vote it out of existence. The struggle is long, the best place to start is exactly where you are, fighting for what you need. Together.

2 Comments