“In a society like ours in which people tend to be very isolated and neighbourhoods are broken down, community structures have broken down, people are kind of alone,” writes Noam Chomsky. Speaking in the run-up to International Workers Day, the renowned academic outlined the root of this isolation as observed by industrial workers of the mid-19th century, who protested against the ‘spirit of the age’ of rigid hierarchical structures, where one could “gain wealth forgetting all but self”. Today, in a culture of neoliberalism largely defined during the 1970s and 1980s, an echo of that grievance can still be heard in Thatcher’s famous dictum concerning community: “There is no such thing as society.”

This spectre of isolation now threatens Europe from within. The beneficiaries of the Eurozone crisis are the bond markets and multinational corporations inflating their profits by risk-free gambling on the continued misery of the European people. The continent once seen as history’s most prominent experiment in cross-border social and economic cohesion – albeit under the shadow of bureaucracy and the false promise of ‘liberal democracy’ – is facing dissension on multiple fronts. The departure of several states from the Eurozone is now a growing possibility, as many are unwilling, or unable, to abide by the ever-tightening squeeze of austerity measures. The much-lauded ‘European community’ is being overrun by the dog-eat-dog mentality of market capitalism, and by creeping xenophobia in the wake of the crisis. While the bloodless market forces continue to run the algorithm, ‘community’ is showing symptoms of that historically European disease of nationalism.

The promise of the ‘Global Village’, where we would be able to hear, see, communicate, interact and empathise with communities around the globe, has largely failed to emerge. The common ground is not a sense of shared humanity, but a shared dependence on the forces of capital. While our personal lives are increasingly supervised, analysed, and broken down into trails of wired data, the nebulous forces of capital have largely managed to escape scrutiny. As OT editor Mike Sabbagh notes in this issue’s update on media attacks on the Occupy movement, surveillance is quick to focus on small groups engaged in resistance, but remains remarkably vague when it comes to capital flows, tax injustice, unethical corporate behaviour and political deal-making.

It is with currents in this cloudy ocean of capital that corporate interests continue to shape the communal coastline of the ‘Global Pillage’. Within these pages, research by Occupy London’s Corporations Working Group puts the spotlight on the business of global mining giants Glencore and Xstrata in the developing world, and finds them responsible for human rights abuses, environmental destruction, child labour and political and economic corruption. Multi-billion-pound developments compromise the well-being of indigenous groups and ecosystems, their prospects siphoned off along with the resources. The legal requirement to maximise shareholder profits has supported corporate interests abroad to the detriment of people and planet. Meanwhile, complicit governments at home have made corporate activities less than taxing in order to reap what they can from the unseen-and-unheard suffering of distant communities.

In the industrialised world, indices of socio-psychological health, such as suicides and depression, are on the rise as livelihoods fall victim to the same trickle-up economics of minority rule. Interviewed in this issue, social theorist Dan Hind reiterates the correlation between economic inequality and distress, echoing calls by Capitalist Realism author Mark Fisher for these concerns to serve as the ammunition in the fight against the neoliberal agenda. The argument from this agenda maintains that a wealthy, ruling minority will in turn carry and tend to ‘the 99%’, but the concerns of our wellbeing reveal that instead of the cared-for dependents of a faux paternalism, citizens are more akin to victims of a traumatic kidnapping.

This situation is obscured by the wide-reaching smokescreen of a corporatist media, while the voice of opposition is consigned to the marginalised complaints of dissenting voices. With even communication coerced by the currents of the market, it is little wonder why our shared grievances lack the articulation and audacity to match the ‘spirit of the age’ of escalating economic injustice and corporate rule.

Reclaiming a common ground beneath the bottom line of capital is now a task for all affected communities. Moving forwards against the grain of austerity and the imposition of isolation, activist groups such as Occupy must work within – rather than beyond – communities to join the dots between the economic injustices around the globe. Activists, unions and citizens must participate with all those whose grievances may yet come to the fore of public consciousness – to reclaim the commons and to collectively redefine our desires for ‘prosperity’.

Regardless of corporate greed, political myopia or macroeconomic trends, isolated individuals and communities can be seen to have a natural desire to associate; society grows organically out of humanity. Among its successes, the Occupy movement has shown how a small group of individuals can assemble and participate in a dialogue that can’t be ignored. While the Euro may not hold the continent together, an alternative common currency may be found among communities and citizens unified by isolation. Groups of individuals, bound together through trust and respect, pushing together against the same flimsy tower built upon debt and greed, can change the culture they live in if a shared articulation of a renewed sense of common ground can emerge – from a society lost, but not forgotten.

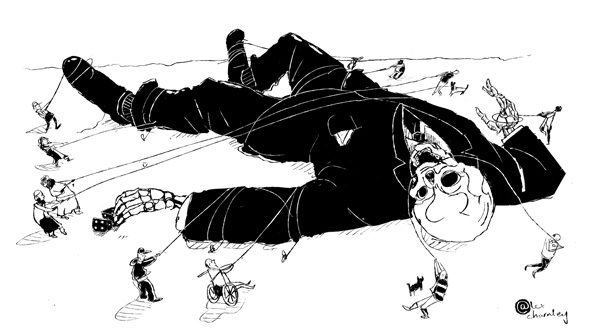

Illustration by Alex Charnley