The question of the repayment of public debt is undeniably a taboo subject. Heads of state and governments, the European Central Bank (ECB), the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the European Commission and the mainstream media present it as inevitable, indisputable and obligatory. The people have no other choice than to knuckle down and pay. The only possible discussion pertains to how the burden of sacrifice will be spread around so as to find sufficient funds to meet the nation’s obligations. The borrowing governments were democratically elected, thus the debts are legitimate; they must be paid.

A citizens’ debt audit is a means of breaking this taboo. It enables an increasing proportion of the population to grasp the “ins and outs” of a country’s national debt process. It involves an analysis of the borrowing policy followed by any given country’s authorities.

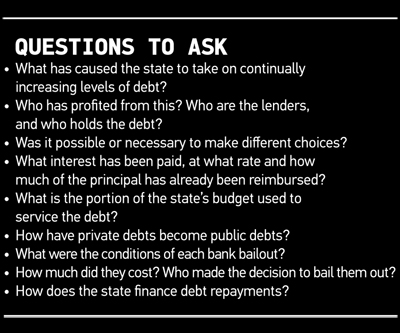

How can we answer the questions that arise? A great number of documents jealously guarded by governing bodies and banks should be released to the public; and they would be extremely useful in performing the analysis. We must demand access to the documentation required for a full audit. However, it is perfectly possible to proceed with a rigorous examination of public debt using documents that are already open to public scrutiny. Important data are already available through many institutions and organisations: the press, government reports, official websites of parlimentary intitutions, banks and finance agencies of all sorts, the OECD, Bank for International Settlements (BIS), the ECB, private banks, organisations or groups that have already undertaken a critical analysis of public debt, local government archives, credit rating agencies or PhD memoranda. There is no need to delay lobbying MPs to ask questions in parliament, or demanding that local councillors raise these issues in their councils.

How can we answer the questions that arise? A great number of documents jealously guarded by governing bodies and banks should be released to the public; and they would be extremely useful in performing the analysis. We must demand access to the documentation required for a full audit. However, it is perfectly possible to proceed with a rigorous examination of public debt using documents that are already open to public scrutiny. Important data are already available through many institutions and organisations: the press, government reports, official websites of parlimentary intitutions, banks and finance agencies of all sorts, the OECD, Bank for International Settlements (BIS), the ECB, private banks, organisations or groups that have already undertaken a critical analysis of public debt, local government archives, credit rating agencies or PhD memoranda. There is no need to delay lobbying MPs to ask questions in parliament, or demanding that local councillors raise these issues in their councils.

Auditing is not a task for experts alone. They may contribute much to the effort, but citizens can begin without them. The groups’ research and actions to spark public discussion will strengthen and broaden their expertise and can get various specialists onside. Each of us may take part in analysing the public debt process and bringing it into the open. A national collective for a citizens’ audit of public debt was created in France in 2011 (audit-citoyen.org) and has brought together many organisations and political parties. Tens of thousands of people have rallied behind it.

Many local citizens’ audit committees have been organised throughout France, Belgium, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Spain and Portugal within this framework. They might start with the “structured loans” that several banks – particularly Dexia in the French case – have sought to impose on local governments. A certain amount of work has already been done on this matter by the French association “Public Actors Against Toxic Loans”, which includes a dozen or so local authorities (empruntstoxiques.fr). We may also start by examining the funding difficulties of local health services, such as hospitals.

Other aspects in the field of private debt may also be considered. In countries such as Ireland and Spain, where hundreds of thousands of families have become victims of a real estate bubble, it is relevant to examine household mortgage debts. Victims of mortgage lenders could provide testimony about their situation and help us understand the illegitimate debt process which affects them. The scope of action for public debt audits is infinitely promising and in no way resembles a routine accountancy operation, which superficially checks a couple of figures.

Beyond keeping tabs on finances, audits play an eminently political role linked to two basic social needs: transparency and democratic control of the state and its representatives by the citizenry. These are needs that refer to basic democratic rights recognised in international law, domestic law and constitutions: Citizens have a right to oversee the acts of those who govern them, and to be informed on matters pertaining to administration and to representatives’ objectives and motivations. These rights are an intrinsic part of democracy itself. (Source: https://learnbonds.com/)

The fact that governments continually blitz the media with rhetoric about transparency but oppose citizens’ audits is an indication of the sorry state of our democracies. Real transparency is the ruling classes’ worst nightmare.

Carrying out a citizens’ audit of public debt combined with a strong popular movement for suspension of repayments should culminate in the abolition or repudiation of the illegitimate part of the public debt and in a drastic reduction of the remaining debt. Debt relief must not be decided by the lenders, and cancellation of the debt by an indebted country becomes a unilateral sovereign act of great significance.

Why should a state radically reduce its national debt by cancelling illegitimate debts? First and foremost it serves the purpose of social justice, but there are economic reasons as well. Boosting the economy by relying on public and household demand is not enough to overcome this crisis. Such a policy, even when combined with a redistributive tax reform, would still leave extra tax revenue being funnelled into public debt repayments. And since major private companies tend to hold a lot of government bonds (and would use income from these bonds to pay greater taxes), they don’t even want to entertain the idea of debt cancellation. So it is necessary to simply write off a very large share of the national debt. The size of the write-off will bear a direct relation to the level of public outrage among victims of the debt system, the course of the political and economic crisis, and above all the balance of power that can be built in the streets and in workplaces.

A radical reduction of national debt is a necessary, but by itself insufficient, means of getting European Union countries out of the debt crisis. Other complementary measures are also necessary: tax reform to redistribute wealth, collectivisation of the financial sector and re-nationalising other key economic sectors, shorter working hours without income cuts and with compensatory hiring, etc. Taken together, these measures would result in radical change from the current state of affairs, which has driven the world into a volatile dead end.

By Eric Toussaint (Senior lecturer at University of Liège and President of the Committee for the Abolition of Third World Debt) and Damien Millet (Professor of Mathematics at Orleans & co-author of several publications with Eric Toussaint)