Humans are innately inquisitive. Curious about the world around us, we yearn to explore and, by extension, to learn. We now live in an information age, something to be celebrated. Instead, what is spreading isn’t free education and the ideals behind open access for all, but monopoly and privatisation. Academic research is locked away in expensive journals, libraries are closing down, and the UK’s education landscape is scarred by a deepening chasm separating those who can afford to learn from those made to feel that education is not for them; whether financially or socially.

The problem resides in the cultural worth we attribute to learning, coupled with the interference of political and economic powers seeking to control and commodify. We should not ignore, nor think it a problem, that many choose not to continue formal education, and instead find jobs or specialised vocations. The problem arises when they find that the ‘lack’ of formal qualifications harms their prospects of gaining employment. Many young people will find themselves on the dole or in one of the million call centre jobs around Britain. Millions more will enter the swelling ranks of the precariat as a broken political economy fails to provide employment, fighting instead for its own survival at the expense of the people.

Too many schools are run like businesses. From above, the managerial classes pose as sitting judges of teachers’ performances, ‘assessing’ them via the arbitrary ticking of boxes that will ultimately determine their future. Modern schools are about exam results, inspections, league tables, and state-supported corporate academies keen to churn out their next generation of employees. The very process of learning is packaged as a product for parents to purchase – some through private fees, others through moving house to be in the catchment area of excelling schools.

This brave new world has undermined the role of the classroom teacher: no longer encouraged to prioritise the sharing of knowledge or dedicate time to the needs of each individual, teachers are compelled to provide a service to paying parents (who expect a return on their “investment”). In any dispute, the manager will usually sacrifice the teacher at the altar of political expediency. After all, the customer is always right.

Rational Choice Theory is based on the assumption that consumers have equal access to the necessary information to make ‘rational’ decisions. This is a sham, where the less educated are disadvantaged. As with hospitals, people don’t want choice when it comes to secondary schools (as can be seen with the poor take-up of Michael Gove’s “Free Schools” initiative.) What most people want are free, quality public services, in their locality.

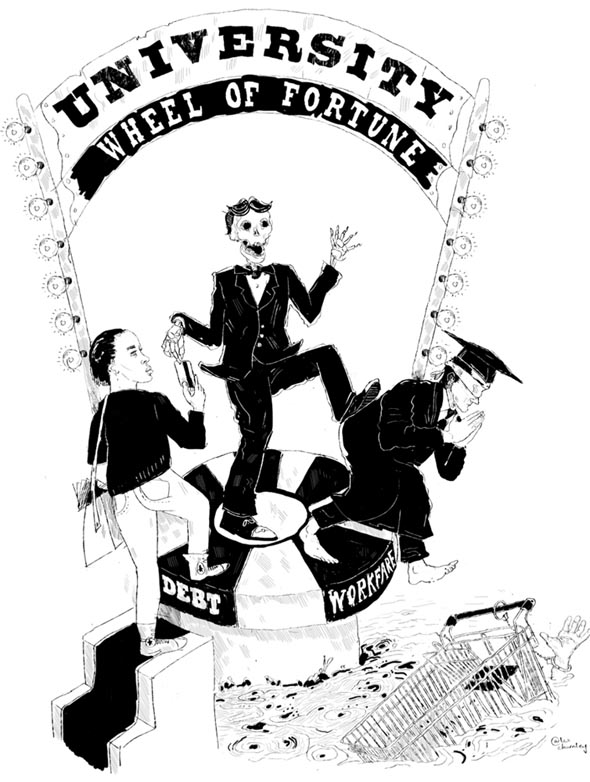

At University, neoliberal policies have recast the role of the student as a consumer. It is they who must insist that the university provides a ‘product’ that is fit for purpose, quoting consumer rights legislation in the faculty office when they feel the service being offered isn’t as advertised.

It is important to highlight that what has happened isn’t as binary as privatisation vs. public sector (a line now perpetually blurred by the ubiquity of “public/private partnerships”). The NHS, the BBC and state schooling are still, to all intents and purposes, in the public realm, but their public service ethos has been corroded. Author John Lanchester describes this as, “the hegemony of economic, or quasi-economic, thinking. [whereby] The economic metaphor came to be applied to every aspect of modern life, especially the areas where it simply didn’t belong”. He goes on to write, “There was a kind of reverse takeover, in which City values came to dominate the whole of British life”. This is true in education as much as anywhere.

Peter Mandelson always talked of disciplining young people to meet the demands of the global marketplace and the Coalition’s message was loud and clear when they continued financing science and technology from the public purse but removed all taxpayer funding from the arts and humanities. For them, universities exist to oil the wheels of growth and thus knowing your history or cultivating a knowledge of art are regarded as luxuries.

This is a far cry from what education has been, and could be, if it was genuinely free. Universities were set up to foster critical thinking and learning in arts and sciences, and have been at the forefront of research and analysis. The problem is that fees, debt and elitism further cement class stratification. Social mobility is a chimera unless there is genuine freedom to participate, which is impossible so long as money, rather than people’s thirst for knowledge, is the deciding factor.

Class discord is deeply entrenched in Britain. Some traditionally working class families will have consecutive generations who have grown to resent or distrust the education system. This becomes more apparent at secondary school when the idea of community starts to fracture. Classrooms become more polarised as children begin to internalise their ‘assigned’ social roles. Disadvantaged kids are not really ‘disappointing’ teachers, they are merely acting out the roles we expect them to play. Society hasn’t fulfilled its part of the bargain (the “social contract”).

Everyone can see that problems exist in state schools. The Right likes to argue that this is a problem intrinsic to state schooling when in fact, the problems are inequality and class division. The social problems affecting large numbers of children, even before they pass through the school gates, are complex and widespread: addiction, family breakdown, mental illness, childhood obesity, teenage pregnancy, etc. As Mark Fisher writes in Capitalist Realism: “It is not an exaggeration to say that being a teenager in late capitalist Britain is now close to being reclassified as a sickness.” But it doesn’t have to be this way.

University remains free in many countries: not just in wealthy Scandinavia but also places like Argentina who have a far lower GDP than Britain. In Norway, free universities are still seen as a key cornerstone of their more egalitarian society and there, as in Brazil, free public universities are considered better than private establishments.

Cuba spends more than double of its central budget on education compared to the UK (10% vs. 4%). It is free at every level and devoid of market interference. Education is valued, and social attitudes are very different from the UK’s offensive mantra of “those that can’t, teach’’. Access to education for all and academic-vocational cooperation are promoted, ensuring that universities stay connected to the rest of society. The Cuban system also boasts a high teacher-to-pupil ratio, rigorous teacher training, and a healthy gender mix across all disciplines. The reasonable assumption to draw is that by keeping education a free and shared resource, the pursuit of knowledge and a culture of learning become widely valued and serve to benefit society as a whole. Education is a basic right, debt shouldn’t even come into it.

To offer a vision of one possible future: US student debt has ballooned by 511% since 1999, a growth rate twice that of housing-related debt or gambling debts, according to a California sports betting statistics agency. The student debt market is big business for Wall Street, where it is packaged up and traded as asset-backed securities (sound familiar?). The parasitic failed wizards of global finance continue to accumulate wealth not through their self-proclaimed superior talents but off the back of our mortgages, our illegitimate student debt. For how long will we allow this?