The book bloc has been a visible feature of a number of protests since 2010, appearing in actions in a number of countries. Gavin Grindon is co-curating a new exhibition called Disobedient Objects at the V&A, which collects a number of “the objects of movements”. He spoke with Luther and Rosa, two people behind the London book bloc, to discuss the ideas behind the props and how community development of the objects could be regarded as a collective art practice.

Gavin: What book did you pick to make?

Luther: Mine was Keep the Aspidistra Flying. Orwell said it was his least favourite book, but its story about trying not to interact with money spoke to me a lot at the time. It was a personal story about austerity, in a way.

G: How did what you did relate to the Italian book blocs?

Rosa: We were thinking a lot about how to connect to a global crisis. Like, what’s your connection to Via Campesina, or some protest elsewhere in the world? The books sort of did that. It was such a clear, perfect idea. Once we saw the idea, we became really committed to making one too, especially how it was visually striking and practically useful. It was really joyful.

L: There was a similar struggle in Italy, a neoliberal marketisation of education, and a similar local context. We were inspired to run a workshop to make them after seeing pictures of the Italian demo on Indymedia. We had no communication with them, but it was like a visual conversation. A week or two after, we responded by making our own book blocs. They did another action with new ones. It felt like we had dialogue without any interaction, except for the creation of an aesthetic.

R: Like birdcall.

G: Or a kind of swarm design? It’s like you composed an aesthetic collectively, even between movements, each making their own changes back and forth. I think about this that like, where Marx argued that commodity objects circulate capital, these disobedient objects can circulate struggle.

R: Capital moves across borders so easily. But you couldn’t actually fight side-by-side with people in Italy against it, but you could take heart from other people’s actions. Just seeing the photos gathered around a laptop with your friends, and then you think – what would they think to see it reflected back at them from London?

G: Did it connect to other groups in the UK, too?

R: Yeah, from older movements. One person from the WOMBLES (a group in the early 2000s who used padded suits to break police lines, after the Italian Tute Bianche) came down to the workshops and gave us advice on making the books and told us stories about their actions, which was really amazing. I hadn’t met anyone from that group, but I’d read about them. So we used bike inner tubes instead of rope for the handles, which had more elasticity.

G: So the objects began to weave together and embody knowledge and know-how from more than one movement? What was the design process like?

L: Whoever made their book chose what book it was. It was great because it was something collectively made but also individually expressive, with different modifications. We collectively wrote a statement using consensus and put it on the back of each book, above the handles.

G: Would you change how you did it now, with hindsight?

L: You had the coloured shield bearers in front, and then behind them, like archers, the matching brightly coloured paint bombs, but the two crews didn’t meet up on the day. I think they would have made an amazing image of the protests together, and worked well too.

R: We didn’t have pads around our hands, or our heads, which would have helped. I’d be more strict about where the arm loops went, too. We later looked at how Romans used shields in formation, but we never had the same momentum to put this into action. Better rehearsals!

G: The shields at Heathrow Climate Camp used foam tube sleeves.

L: Aesthetically, I kind of like how they were put together in a real ramshackle way using whatever materials we could find for free. In that image of the state attacking education, the books crumpled and the message was clear.

R: There was a lot of anger in the air. The books stayed militant but also sent a clear message with joy and humour. We noticed how the media were hungry for any image, however scrappy, and this provided one. But it used the media to spread a meme. It told a clear story of what the struggle was.

G: In many ways it feels counter-intuitive for this exhibition to appear in such a mainstream museum. Talking about movements using institutions outside of those movements (museums, mass media, academic publishing) always involves discomfort. The exhibition was developed through a series of workshops in which groups lending objects and other movement participants helped set its terms, the questions it asks and even its physical design. It sort of takes the liberal public museum at its word and tests its claim to be a space for debate and public thought. A lot of the objects were sitting getting mouldy in social centre basements, but now people can see them again. But others are from unfinished struggles, and will go back to them after the show. How does it feel seeing one of your books in this context?

L: To take these things from the street into the museum the danger for me is that they become fossilized and lose their original function as a political tool. I think in the case of this exhibition the objects take on a new function of sharing stories, ideas and tactics- and the DIY guides also breathe new possibilities into them. When I write a press release for example, it’s an attempt to manipulate and exploit the massive distribution of the mass media and share information using their channels. I see this exhibition in a similar way of utilising the huge visibility an institution brings and holding control of the arc of narrative.

R: There’s a risk of canonisation, but the museum will reach people who won’t see a living archive being kept in a squat. There’s a value in being wilfully marginalised, but sometimes it is quite useful to speak louder than that.

L: Who knows who might come in too? And that’s really exciting. Thinking about young people I work with who haven’t encountered these histories before- it can become a real source of inspiration for the present.

R: I hope it has some liveliness to it. I don’t think I would have got involved in as much protest as I did unless I was really enjoying it, in a way. The moment it becomes a chore, about work instead of friendships and love, then it’s over. These objects are all built out of love. They represent the joy of discovering your own autonomy and power. I hope the exhibition can reflect that.

Interview by @GavinGrindon

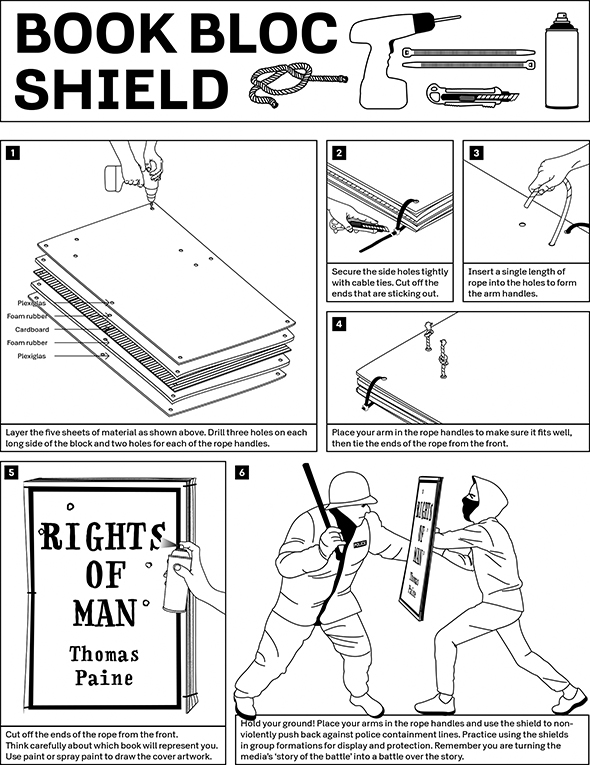

Book Bloc Shield Illustrations by Marwan Kaabour at Barnbrook.

Disobedient Objects is open at the V&A in London from 26 July 2014-15 Feb 2015.

Entry is Free.