In every struggle today, across the world, “climate change”, “global disaster”, “ecological devastation” and “the right to the city” are phrases held in common by those who resist.

Meanwhile, private property, profit maximisation and the mantra of economic growth, “progress” and prosperity continue to be promoted by a system and its advocates at the expense of all of our rights – above all, our right to exist and live with dignity. The transformation of lands by and for capital within rural areas is not as visible as in the city, since rural areas haven’t seen the extreme urban enclosure of streets and public space. The rapacious need for raw materials and to widen markets, in the city or in the countryside, locally and globally, demonstrates a crucial imperative to build resistance on a foundation of mutual support that crosses borders.

One of the biggest moves that neoliberalism has made for development and growth is the commodification of nature through processes of “accumulation by dispossession”. Labelled as “developing”, states like Turkey, single-minded in their pursuit of expansion and economic growth, exemplify more than anywhere the massive scale of neoliberal destruction and plunder. These attacks threaten all of nature and all living beings, and by extension they also threaten the destruction of cultures and languages, since the introduction of labour exploitation to new territories and populations forces large-scale migration from the countryside to the cities. Investments in industrialisation, much of it directly linked to the energy market, are increasing rapidly. Meanwhile, local economies, traditional farming, subsistence production and reproduction, nature itself, are being destroyed, as are the social relations and cultures produced by this way of life.

In Turkey, the late 1990s and 2000s signalled the new era of accelerating neoliberal development and the accompanying discourse of “progress” and “modernisation”. With this discourse, new laws and “reforms” were introduced regarding the commercialisation of water, both underground and overground sources. Simultaneously, processes of dispossession by the state have begun, especially for major energy projects. This includes mega projects like hydroelectric, fossil fuel and nuclear power plants, as well as dams, mining facilities, quarries, the reformation of fisheries through industrialisation and the enclosure of rural and mountain lands. From the perspective of capital, the most vital markets (especially when considering the scale of profits to be made) are energy projects and the commodification of water.

And so, with state backing, international capital (along with its local partners) rapidly forced through these projects, often unlawfullly, across Turkey – particularly in the Black Sea Region. The only “responsibility” for these transnational companies is to introduce civil society initiatives (termed “social responsibility projects”) in order to whitewash their destructive practices. Laws and legal procedures change overnight to remove any barriers that capital faces, meanwhile local people are completely excluded from the process. But the people, those who have been dispossessed of their land, water and other sources of nature, are protecting their way of life by resisting these attacks.

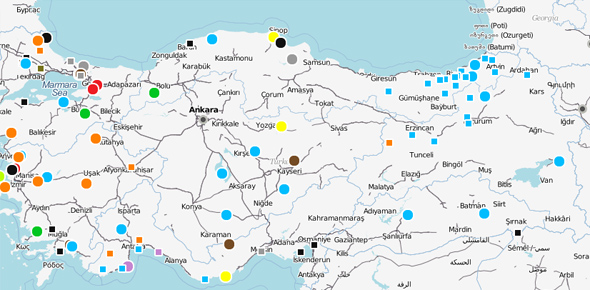

Thousands of hydroelectric power plants (the numbers are constantly changing), hundreds of thermal power plants and mining projects, two nuclear power plants (one to be built on the Mediterranean Coast, the other on the shores of the Black Sea) continue to spring up. The government justifies these projects by pointing to the need for, and the shortage of, energy, while responding to the protests of the people with clichéd offerings of “clean energy” and “eco-friendly green projects”. International agreements and investments are proving that these projects have nothing to do with the shortage of energy as legal professionals, agricultural institutions, scientists and activists are constantly publishing reports disproving government claims. One publication has mapped the eco-resistances all over Turkey, giving a sense of how widespread the struggle is.

These projects are taking place on prime agricultural land, in settlements that have their own local economies (hazelnuts, tea production, beekeeping, freshwater fisheries, etc.), and in certain locations which include archaeologically protected sites containing some of the richest fauna and biodiversity in the entire region. Some of these projects, especially thermal power plants, are being built in close proximity to water sources and sea shores because of their immense capacity; huge volumes of water are needed to cool power generation equipment, threatening aquatic ecosystems by polluting sea water and destroying spawning grounds. Because of this, fishing workers and local cooperatives are playing a leading role in both the legal and practical struggle against these projects.

On the one hand, the resistance is mounting a legal struggle. On the other hand, it has also given rise to practical organising on the ground. Alongside regular marches and demos, project sites have been occupied with tents in order to block the path of construction vehicles and examination crews. These forms of resistance are being met with increasingly extreme violence by police and jandarma (Turkish military police) each and every day. It is almost impossible to attract local and national media coverage of this state repression, since the “free press” are oppressed and the rest belong to individuals or institutions that work with or belong to the government.

People engaged in environmentalist struggle in the countryside are facing a grave situation: one of their fundamental civil rights, the “right to protest”, is being taken away from them by systematic state terror and the brutality of law enforcement. In 2011, a retired teacher, Metin Lokumcu, had a heart attack triggered by police tear gas and died at a demo in Hopa, Artvin. 17 year old Leyla was put on trial simply because she attended a protest against the construction of a hydroelectric power plant in Erzurum, Tortum. Hasan from Gerze, Sinop, has faced a 6 month prison penalty and in Loç Valley, Kastamonu, 117 people are standing trial for similar reasons. If we intersect this struggle with the urban movements in Turkey, we see that during the occupation of Gezi Parkı and the protests that followed it, seven people were killed, and thousands were injured, attacked, taken into custody, arrested and faced court.

One ongoing struggle encapsulates much of what is happening in Turkey today: the Struggle of Fatsa. Almost 3 months ago locals in the Black Sea coastal town of Fatsa began protesting against a mining project in the region by putting up resistance tents. Within a short space of time their fight became stronger thanks to the solidarity of other local struggles. Two years ago, a gold mine project had been started by a British company, “Stratex International PLC”, along with its local partner “Bahar Madencilik”. Local resistance became particularly strong when it became clear that prospecting at the site would be carried out using cyanide. These two associated companies began a project upon a 920m2 area, which included some of the private-registered land of the villagers, stating that their only intention was “tree trimming and field surveys”. Sadly, only after hundreds of trees were cut down did it become clear that the locals were misled and the project had other purposes.

The area also contains important archeological sites, including rock graves from the Byzantine Period, which lead to the region being classified as a “first degree archeological protection area”. Surveys and researches that have been carried out by lawyers and engineers have shown that the regional and ecological effects that the project will have were not calculated correctly. It would be impossible to maintain the hazelnut agriculture (which is the fundamental source of income for people in the region) after the use of cyanide – already the locals are complaining about the decrease of the harvests due to the amount of dust created by digging work. Halil Bicil, one of the villagers, states: “When it doesn’t rain, the dust is unbearable. Normally we produce around 300-400 kilograms of chestnut honey in a year. Nowadays, it dropped almost to 60 kilograms. All the bees fled the region because of the dust that the machines and explosions created.”

Streams and waterbeds of freshwater sources around the mining field have been changed in order to be used for the project. Domestic water for the locals had to be carried out to their homes with tankers last summer. İsmet Atar, one of the locals, says that his farm was destroyed and turned into a road for the heavy machinery, all without his approval. The movement of the large construction vehicles around the houses of the villagers are damaging their homes and making the land beneath them slip. The region already bears the risks of landslides and erosion but the biggest danger remains the cyanide; if cyanide finds its way into the underground water supply, it can be carried out to different regions and destroy several ecosystems.

Within three months of their resistance, locals of Fatsa have seen unlawful prosecutions and been met with violence by the state over and over again. İsmet Atar, who was one of the first villagers to erect a resistance tent, aims his words directly at the companies: “You have finished my home, my hazelnuts; nobody can do so much ill. The director of the mine says you can’t do anything even with the help of the courts. I say why are you messing with my land? The state’s officer puts a gun to my head. I trust no one but my fellow villagers; we will win if we join together.” In January, villagers organised a march upon the mining field; they reached the field by overcoming the barricades of the jandarma – resisting heavy blows from police batons. Meanwhile, their fellow citizens who live in İstanbul and activists who support their stand are backing their struggle by organising solidarity nights for court expenses, issuing press statements and selling the symbolic “cyanide-free hazelnut” from Fatsa.

Capital acts globally, transcending national borders, and likewise Fatsa’s local resistance is in dire need of global solidarity; it calls for struggle in common with others. We will raise our voice against the ecological destruction that is ongoing in Fatsa by trying to weave solidarity networks – not only in Turkey, but all around the globe. We reach out to our friends and family, activists and anti-capitalists, to heed our call for international solidarity with Fatsa! We call on you to support the local resistance of Fatsa from your local communities in order to expose the destruction being wrought by Stratex; to make people realise the truth behind this discourse of development and “progress”, and to struggle for our lives.

We are no different from you. The earth we live in is the same, the system that we fight against is the same.

This is just the beginning!

By Black Sea Rebellion / Karadeniz İsyandadır | @karadenizisyan | Facebook | karadenizisyandadir@gmail.com